GD-150: Designing and Implementing a Bioassay Program

Preface

This guidance document provides information for designing and implementing a bioassay monitoring program in accordance with the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) and the regulations made under the NSCA.

This guide offers fundamental concepts in determining the need for a bioassay program, selecting participants for the program, and determining the optimal sampling frequency. This guide also suggests methods of interpreting results.

Key principles and elements used in developing this guide are consistent with national and international standards, guides, and recommendations, for example: DOE Standard Internal Dosimetry (DOE-Std-1121-98), from the U.S. Department of Energy; American National Standard-Design of Internal Dosimetry Programs (ANSI/HPS N13.39-2001) from the Health Physics Society; and Safety Guide RS-G-1.2, Assessment of Occupational Exposures Due to Intakes of Radionuclides, from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Nothing contained in this guide is to be construed as relieving any licensee from pertinent requirements. It is the licensee's responsibility to identify and comply with all applicable regulations and licence conditions.

Contents

B.1 Example 1: Determining Participation in a Bioassay Program

B.2 Example 2: Determining the Counting Error (Uncertainty)

B.3 Example 3: Determining the Monitoring Frequency for Intakes of 137Cs

B.4 Example 4: Determining the Monitoring Frequency for Intakes of 131I

B.5 Example 5: Derived Investigation Levels for 137Cs Inhalation

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Purpose

This guidance document provides information for designing and implementing a bioassay monitoring program in accordance with the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA, the Act) and the regulations made under the NSCA.

1.2 Scope

This guidance document offers fundamental concepts in determining the need for a bioassay program, selecting participants for the program, and determining the optimal sampling frequency. This guide also suggests methods of interpreting and recording results.

1.3 Relevant Regulations

The provisions of the NSCA and the regulations made under the NSCA relevant to this guide are as follows:

- Section 27 of the NSCA states, in part, that "Every licensee and every prescribed person shall (a) keep the prescribed records, including a record of the dose of radiation received by or committed to each person who performs duties in connection with any activity that is authorized by this Act or who is present at a place where that activity is carried on, retain those records for the prescribed time…";

- Paragraph 3(1)(e) of the General Nuclear Safety and Control Regulations states that "An application for a licence shall contain the following information: … (e) the proposed measures to ensure compliance with the Radiation Protection Regulations…";

-

Section 28 of the General Nuclear Safety and Control Regulations states that:

"(1) Every person who is required to keep a record by the Act, the regulations made under the Act or a licence shall retain the record for the period specified in the applicable regulations made under the Act or, if no period is specified in the regulations, for the period ending one year after the expiry of the licence that authorizes the activity in respect of which the records are kept.

"(2) No person shall dispose of a record referred to in the Act, the regulations made under the Act or a licence unless the person (a) is no longer required to keep the record by the Act, the regulations made under the Act or the licence; and (b) has notified the Commission of the date of disposal and of the nature of the record at least 90 days before the date of disposal.

"(3) A person who notifies the Commission in accordance with subsection (2) shall file the record, or a copy of the record, with the Commission at its request"; - Subsection 1(2) of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "For the purpose of the definition ‘dosimetry service' in section 2 of the Act, a facility for the measurement and monitoring of doses of radiation received by or committed to nuclear energy workers who have a reasonable probability of receiving an effective dose greater than 5 mSv in a one-year dosimetry period is prescribed as a dosimetry service";

- Subsection 1(3) of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "For the purposes of the definition ‘nuclear energy worker' in section 2 of the Act, the prescribed limit for the general public is 1 mSv per calendar year";

- Paragraph 4(a) of the Radiation Protection Regulations states, in part, that "Every licensee shall implement a radiation protection program and shall, as part of that program, (a) keep (…) the effective dose and equivalent dose received by and committed to persons as low as is reasonably achievable, social and economic factors being taken into account, through the implementation of … (iii) control of occupational and public exposure to radiation";

- Subsection 5(1) of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "For the purpose of keeping a record of doses of radiation in accordance with section 27 of the Act, every licensee shall ascertain and record (…) the effective dose and equivalent dose received by and committed to that person";

- Subsection 5(2) of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "A licensee shall ascertain (…) the effective dose and equivalent dose (a) by direct measurement as a result of monitoring; or (b) if the time and resources required for direct measurement as a result of monitoring outweigh the usefulness of ascertaining the amount of exposure and doses using that method, by estimating them";

- Section 8 of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "Every licensee shall use a licensed dosimetry service to measure and monitor the doses of radiation received by and committed to nuclear energy workers who have a reasonable probability of receiving an effective dose greater than 5 mSv in a one-year dosimetry period";

-

Section 19 of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "Every licensee who operates a

dosimetry service shall file with the National Dose Registry of the Department of Health, at a frequency

specified in the licence and in a form compatible with the Registry, the following information with respect to

each nuclear energy worker for whom it has measured and monitored a dose of radiation:

- the worker's given names, surname and any previous surname;

- the worker's Social Insurance Number;

- the worker's sex;

- the worker's job category;

- the date, province and country of birth of the worker;

- the amount of exposure of the worker to radon progeny; and

- the effective dose and equivalent dose received by and committed to the worker; and

- Section 24 of the Radiation Protection Regulations states that "Every licensee shall keep a record of the name and job category of each nuclear energy worker."

2.0 Monitoring Programs and Selecting Participants

The primary objective of a bioassay monitoring program is to ensure the safety of workers and to assess a worker's body burden from exposure to radionuclides.The principal components of a bioassay monitoring program are the criteria for participation in the program, the frequency of monitoring, and the actions taken on the basis of measurement results.

Four types of monitoring programs are described in this section: baseline bioassay assessment, routine bioassay monitoring, special bioassay monitoring, and confirmatory monitoring. Section 3.0, Method and Frequency of Bioassay and Section 4.0, Interpretation of Results describe the frequency of monitoring and interpreting results.

2.1 Baseline Bioassay Assessment

Baseline bioassay assessment consists of assessing a worker's previous body burden from radionuclides of interest. The type of baseline assessment should be relevant to the radionuclides for which the worker will be routinely monitored. Baseline assessments should be completed at the start of employment or before performing work requiring routine bioassay monitoring. This assessment determines the worker's previous exposure to radionuclides due to previous work experience, medical procedures, natural body levels, etc. (this level is often referred to as "background").

Radionuclides that cannot feasibly be monitored by bioassay, such as radon and radon progeny, are monitored by air sampling. However, note that the purpose of baseline bioassay assessment is to assess the amount of radionuclides in a worker's body as a result of intakes prior to the start of employment. Workplace air monitoring does not provide this information. When workplace air monitoring is the only means of assessing intakes of radionuclides, baseline bioassay measurements are not performed. Information about past intakes may need to be obtained from the previous employer. [1]

The concept of establishing a baseline does not necessarily mean that baseline bioassay measurements be obtained. Administrative review of the worker's history may lead to the conclusion that baseline measurements are not required because the expected results are readily predictable (for example, no detectable activity, or existing exposure history). Such a review may constitute acceptable baseline assessment [1].

Baseline bioassay assessment is appropriate for any of the following circumstances [1, 2]:

- The worker has had prior exposure to the pertinent radionuclides and the effective retention in the body might exceed the derived activity;

- The exposure history is missing or inconclusive; or

- The worker will be working with radioactive nuclear substances that may be detectable in bioassay due to non-occupational sources.

2.2 Routine Bioassay Monitoring

Doses resulting from intakes of radionuclides should be assessed for all workers who have a reasonable probability of receiving a committed effective dose (CED) exceeding 1 mSv per year. These workers are designated as nuclear energy workers (NEWs).

When workers do not have a reasonable probability of receiving annual doses exceeding 1 mSv, the cost of performing routine bioassay may not always be justified for the doses involved. In such cases, the dose may be assessed by estimation; for example, using workplace monitoring. [3]

The licensee should identify which workers have a reasonable probability of receiving:

- An annual committed effective dose (i.e., resulting from all occupational intakes of radionuclides in one year) up to 1 mSv (non-NEWs);

- An annual committed effective dose greater than 1 mSv and a total annual effective dose (i.e., the sum of the annual effective dose from external sources and the annual committed effective dose) up to 5 mSv (NEWs participating in a routine bioassay program, but not necessarily provided by a licensed dosimetry service); and

- An annual committed effective dose greater than 1 mSv and a total annual effective dose greater than 5 mSv (NEWs participating in a routine bioassay program provided by a licensed dosimetry service). [Radiation Protection Regulations, section 8]

The probability of exceeding 1 mSv per year may be assessed on the basis of the activity handled by the worker, the type of radionuclides involved, the physical and chemical form of the radionuclides, the type of containment used, and the nature of the operations performed. When one type of radionuclide is handled daily (that is, approximately 250 days per year), workers handling the activities in Table 1 should participate in a bioassay program. Note that, to decide on participation, bioassay monitoring results should supersede the data in Table 1.

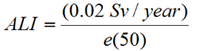

The basis for the values in Table 1 is presented in Appendix A, Selecting Participants in a Routine Program Based on Activity Handled, and can be used to derive site-specific values. Appendix A defines parameters needed to define the Potential Intake Fraction (PIF). Given a particular scenario of intake, the value ALI / PIF represents the activity handled per day of operation that could result in an annual intake equal to the Annual Limit on Intake (ALI), consequently resulting in a committed effective dose of 20 mSv per year. The criterion set for the bioassay participation is 1 mSv. Therefore, the data shown in Table 1 represent the quantity ALI / (20 * PIF).

| Confinement | Volatility | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gases and volatile liquids | Powders | Non-volatile liquids and solids | |

| None | ≥ 2 * ALI | ≥ 20 * ALI | ≥ 200 * ALI |

| Fumehood | ≥ 200 * ALI | ≥ 2,000 * ALI | ≥ 20,000 * ALI |

| Glovebox | ≥ 20,000 * ALI | ≥ 200,000 * ALI | ≥ 2,000,000 * ALI |

| Pseudo-sealed | ≥ 50 * ALI | Not applicable | ≥ 10,000 * ALI |

Bioassay is recommended if the worker is required to wear respiratory protection equipment specifically to limit the intake of radionuclides.

Pseudo-sealed sources [4] are short half-life radionuclides that are handled exclusively in sealed vials and syringes and that meet the following conditions:

- The radiological half-life is less than 7 days;

- The handling of radioactivity is more or less uniform throughout the year;

- The radioactive material is not aerosolized, or boiled in an open or vented container;

- The radioactive material is in the form of a dilute liquid solution; and

- The radioactive material is contained in a multi-dose vial that is never opened and amounts are withdrawn only into hypodermic syringes for immediate injection into another multi-dose vial, or another form of closed containment, or into patients.

The data in Table 1 are provided as generalizations and may not cover all scenarios. It is also assumed that where there are mechanical or other physical barriers in place to protect the worker (such as gloveboxes and fumehoods), the barriers are appropriate for the radioisotope being handled and that they are used as intended and maintained in a proper manner.

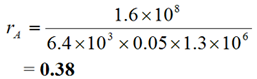

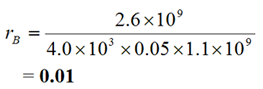

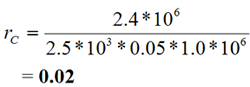

When more than one type of radionuclide is handled, the following steps should be followed to determine if a worker should participate in a bioassay program:

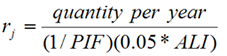

- Calculate the ratio, rj, of the quantity of one radionuclide, j, handled in daily operation to the maximum quantity of that radionuclide that can be handled in daily operation above which bioassay is recommended, from Table 1;

- Calculate this ratio for all other radionuclides handled;

-

Add all of the ratios calculated in steps 1 and 2 above:

R =Σrj

Bioassay should be performed for any radionuclide for which rj ≥ 1. If R ≥ 1, bioassay should be performed for any radionuclide for which rj ≥ 0.3 [4, 5]. In situations where R < 1 but any of the rj values are greater than 0.3, the licensee may choose to monitor the worker for that radionuclide. A worked example is provided in Appendix B, Examples, Example 1.

The worker may be removed from the routine bioassay monitoring program if there is sufficient evidence that the occupational intake does not have a reasonable probability of surpassing 1 mSv per year. Supporting evidence such as air monitoring should be provided.

2.3 Special Bioassay Monitoring

Special bioassay monitoring is performed in response to a particular circumstance, such as a known or suspected intake of radioactive material due to an abnormal incident in the workplace. Special bioassays are often termed "non-routine" or "ad hoc". Special bioassay monitoring may be triggered by either a routine monitoring result or an abnormal incident suggesting that an action level (as defined in the Radiation Protection Regulations) or the dose limit may have been exceeded. Guidance on special bioassay monitoring can be found in CNSC document G-147, Radiobioassay Protocols for Responding to Abnormal Intakes of Radionuclides [6].

2.4 Confirmatory Monitoring

A confirmatory bioassay program is intended to verify: [1, 7, 8]

- Assumptions about radiological exposure conditions in the workplace;

- That protection measures are effective; and

- That routine bioassay is not required.

It may involve workplace monitoring or limited individual monitoring of workers who do not meet the criteria for participation in a routine bioassay monitoring program. (Note: "confirmatory monitoring" should not be confused with the term "screening", which is sometimes used to refer to routine bioassay monitoring when results are less than the Derived Activity (DA; described in Section 4.2, Putting Bioassay Results in Perspective), and the committed effective dose is therefore not assessed.)

When workers handle or may be exposed to unsealed radionuclides, but do not meet the criteria for participation in a routine bioassay program, intake monitoring may be assessed as part of a confirmatory monitoring program. The monitoring frequency may be the same as for routine monitoring or may vary if potential exposure to the unsealed radionuclides is infrequent (taking into account the biological half-life of the radionuclides).

In a confirmatory monitoring program, workers submit to in vivo or in vitro bioassay (see Methods of Bioassay) and may involve sampling a fraction (e.g., 10% to 50%) of a group of workers.

When the results of confirmatory monitoring exceed the DA, further measurements should be taken to confirm the intake and an investigation should be carried out to determine the cause of the unexpected result. If the intake is confirmed, assumptions about radiological exposure conditions in the workplace and the effectiveness of protection measures in place should be reviewed and the need for involved workers to participate in a routine bioassay program should be re-evaluated. All confirmatory monitoring results should be recorded.

This type of program is particularly suited for radionuclides that are easily detected at low levels relative to the DA.

Confirmatory monitoring should be used to review the basis for a routine monitoring program if major changes have been made to the facility or to the operations at the facility. Also, confirmatory monitoring, consisting of using personal air samplers or individual bioassay measurements, should be used to verify that workplace air monitoring results can be considered to be representative. [8]

3.0 Method and Frequency of Bioassay

A range of bioassay sampling methods can be used (e.g., urine analysis, whole body counting, thyroid counting), according to the type of radioactive material handled and frequency at which workers are monitored.

3.1 Methods of Bioassay

Methods of bioassay measurement are classified in two categories:

- In vivo bioassay refers to direct measurement of the amount of radioactive material deposited in organs, tissues, or the whole body. Common methods are thyroid counting, lung counting, and whole body counting.

- In vitro bioassay refers to measuring the amount of radioactive material in a sample taken from the body. The most common method is urine analysis. Other methods are fecal, breath, and blood analysis.

Several factors should be considered when selecting the method of bioassay monitoring. The first factor is the objective of monitoring—there should be a balance between the needs for intake monitoring and dose assessment [2]. Intake monitoring requires timely information about the occurrence of intakes and should be based on the following indicators of intake, in order of preference:

- Personal air sampler (PAS) or workplace air sampler (WPAS), where air sampling is performed in the worker's breathing zone;

- Nasal swabs;

- In vitro bioassay;

- In vivo bioassay.

The methods for ascertaining dose are, in order of preference:

- In vivo bioassay;

- In vitro bioassay;

- Personal air sampling;

- Workplace air sampling.

In addition to these factors, the physical characteristics of the radionuclides of interest should be taken into account. Some radionuclides emit radiation that cannot be detected from outside the body. In this case, a decay product may be measured, such as 234Th when assessing the 238U lung burden, provided the isotopes are in secular equilibrium.

Alternately, in vitro bioassay may be performed. The preferred method of in vitro measurement also depends on the retention and excretion of the radionuclide of interest, including the predominant route of excretion, e.g., urinary, fecal, breath.

Table 2 illustrates suggested methods of bioassay measurement that may be performed for selected radionuclides, taking into account their physical and metabolic characteristics. Note that Table 2 is not exhaustive and the appropriate methods depend on the physical and chemical form of the radionuclide as well as its route of excretion.

Note: In cases where bioassay is inadequate for the determination of doses, air monitoring data may be used for dose estimation. See Section 3.2, Determining Frequency.

| Bioassay Method | Radionuclide | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) In vivo | |||

| Whole body counting |

51Cr 54Mn 59Fe 57Co, 58Co, 60Co 85Sr |

95Zr/95Nb 106Ru 110mAg 124Sb, 125Sb 134Cs, 137Cs |

144Ce 203Hg 226Ra, 228Ra 235U, 238U 252Cf |

| Lung counting |

14C* 60Co 235U, 238U |

239Pu, 240Pu 241Am |

242Cm, 244Cm 252Cf |

| Thyroid counting | 125I, 131I | ||

| 2) In vitro | |||

| Liquid scintillation counting (β-counting) of urine samples |

3H 14C 32P, 33P |

35S

36Cl |

45Ca 129I |

| Liquid scintillation counting of urine after chemical separation | 14C | 89Sr ,90Sr | 228Ra |

| -counting of CO2 from breath | 14C | ||

| -counting of fecal sample after chemical separation | 14C | ||

| -counting of tritiated water in breath and saliva | 3H | ||

| Gamma spectroscopy of urine samples | 57Co, 58Co, 60Co |

85Sr 106Ru |

125I, 131I 134Cs, 137Cs |

| Gamma spectroscopy of fecal samples (possibly after chemical separation) | 60Co | 144Ce | |

| Alpha spectroscopy of urine/fecal sample after radiochemical separation |

226Ra 228Th, 232Th 233U, 234U, 235U, 238U |

238Pu, 239Pu/240Pu** |

241Am 242Cm, 244Cm |

| Fluorimetry, Phosphorimetry | Uranium | ||

| ICP-MS | 234U, 235U, 236U, 238U | 238Pu, 239Pu | |

| TIMS | 239Pu, 240Pu | ||

* Using a phoswich or germanium detector system.

** Alpha spectroscopy cannot normally distinguish between 239Pu and 240Pu.

3.2 Determining Frequency

When selecting a routine monitoring frequency, the main factors to be taken into account are:

- The workplace characteristics;

- The uncertainty in the time of intake;

- Instrument sensitivity;

- The need for timely information concerning the occurrence of intakes; and

- The cost of implementing the monitoring program.

For each radionuclide in the workplace, the physical and chemical form should be known for both routine and non-routine or accident conditions. These forms determine the biokinetic behaviour of each radionuclide, and therefore their excretion routes and rates. In turn, this behaviour helps to determine the bioassay method.

The retention and excretion depends mainly on the chemical form of the radionuclide. Inhaled compounds are classified into three types, based on their rate of absorption into blood from the lung: F (Fast), M (Moderate), and S (Slow). For example, a type F compound such as UF6 is absorbed into blood relatively quickly from the lungs. Type S compounds, such as UO2, remain in the lungs for a longer period of time. Default lung absorption rates are available in Human Respiratory Tract Model for Radiological Protection, International Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 66, Vol. 24, No. 1-3 [9] for the three lung clearance types and criteria for absorption type classification when site specific data are used to characterize workplace air.

Another factor in selecting a routine monitoring frequency is the uncertainty in the intake estimate, due to the unknown time of intake (see Appendix B, Examples, Figure B3 and Figure B4). For weekly monitoring, there is greater uncertainty in the time of intake in the case of urinary excretion (see Appendix B, Figure B4) due to the larger variation in excretion rate in the first days post-intake. Routine measurement results should be assessed in such a way that the intake is assumed to have taken place at the mid-point in the monitoring period.

Instrument sensitivity has a significant impact on the monitoring frequency. The latter should be selected so as to ensure that significant doses are not missed. A dose could be missed if, following an intake, the body content rendered by excretion rate was reduced to a level less than the instrument's Minimum Measurable Concentration (MMC) during the time between intake and measurement. When practicable, the monitoring period should be such that annual intakes corresponding to a total committed dose of 1 mSv do not go undetected. If this cannot be achieved, workplace monitoring and personal air sampling should be used to supplement intake monitoring. By applying the appropriate metabolic model and assuming a pattern of intake, a suitable monitoring period can be determined.

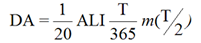

The Derived Activity (DA) (measured as Bq or mg for in vivo bioassay; Bq/L or µg/L for in vitro bioassay) may be defined as follows:

where:

- T

- = the monitoring period, in days

-

m(

)

)

- = the fraction of the intake that is retained in a tissue, organ or the whole body, or excreted from the body, at the mid-point in the monitoring period (see Appendix B, Examples, Figures B1 to B4); a function of time with units of "Bq per Bq of intake" for in vivo bioassay, and Bq/L per Bq of intake for in vitro bioassay

- ALI

- = Annual Limit on Intake, in Bq/year

Values of m( ) can be obtained from

Individual Monitoring for Internal Exposure of Workers, Replacement of ICRP Publication 54, International

Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 78 [7], addressing monitoring for

intakes of radionuclides.

) can be obtained from

Individual Monitoring for Internal Exposure of Workers, Replacement of ICRP Publication 54, International

Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 78 [7], addressing monitoring for

intakes of radionuclides.

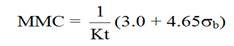

The recommended maximum monitoring period is taken as the time at which the DA is equal to the MMC. The detection limit (i.e., the MMC) [10] can be defined as follows:

where:

- K

- = a calibration factor (K depends on the radionuclide and detection efficiency), measured in (counts × L) / (seconds × Bq)

- t

- = the count time for the procedure, in days

- σb

- = the standard deviation of the count obtained from uncontaminated personnel (total blank counts)

For in vitro bioassay:

K = E V Y e-λΔt

where:

- E

- = the counting efficiency, in (counts) / (seconds × Bq)

- V

- = the sample size in units of mass or volume, in g or L depending on the sample type

- Y

- = the fractional chemical yield, when applicable (no units) (note: if not applicable, Y=1)

- λ

- = the radioactive decay constant of the radionuclide, in 1/seconds

- Δt

- = the time between sample collection and counting, in seconds

For in vivo bioassay, K is the counting efficiency, including a correction for self-absorption when appropriate.

Generally, K must be determined by personnel performing bioassay measurements. More information on MMCs for bioassay can be found in American National Standard-Performance Criteria for Radiobioassay, Health Physics Society [10].

Using this method for monitoring period determination, a recommended monitoring period of one year could be possible for some radionuclides. However, most individuals' retention and excretion rates tend to vary from the model on which the DA values are based. Also, timely information about the occurrence of intakes is needed. There should be a balance between using bioassay as an intake indicator and for dose assessment purposes. To account for this, a monitoring period shorter than one year may be selected depending on other types of monitoring in place (such as workplace air monitoring), and the practicability of carrying out the bioassay measurements. Monitoring periods have been recommended in radionuclide-specific reports (such as for uranium dose assessment [11]). ISO 20553 provides suggestions regarding frequency of testing for various radionuclides and their typical chemical forms [8].

3.3 Other Dosimetric Considerations

In addition to the recommendation that 1/20 ALI intakes be detectable throughout the monitoring period, other dosimetric considerations can be used to help in determining bioassay frequency.

In Individual Monitoring for Intakes of Radionuclides by Workers: Design and Interpretation, Publication 54 [12], ICRP has recommended that the accuracy should be better than a factor of 2 at the 95% confidence level for doses received from external sources of exposure, but that for internal exposures this level of accuracy may not always be possible. Uncertainty due to the unknown time of intake is only one component of the overall uncertainty in the dose calculation. The monitoring periods recommended in Individual Monitoring for Internal Exposure of Workers, Replacement of ICRP Publication 54, International Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 78 [7], accept a factor of 3 uncertainty in intake due to this unknown time of exposure during the monitoring period. If there are several monitoring periods in the year, the overall uncertainty in the annual intake, and committed dose, would likely be less than this factor of 3 [7]. Exposure to some internal sources, such as low levels of tritiated water in some CANDU reactor environments, may occur continually throughout the monitoring period.

In some cases, the best available monitoring methods may still be unable to reliably detect activities corresponding to the 1/20 ALI (1 mSv per year). In these circumstances it is useful to determine the maximum dose that could be missed were an intake to occur at the start of each monitoring period. Such an approach provides a useful perspective for some internal hazards that are difficult to detect [13] but can become overly conservative, particularly when there are several monitoring periods per year.

4.0 Interpretation of Results

4.1 Reference Levels

A reference level is the value of measured quantities above which some specified action or decision should be taken in order to avoid the loss of control of part of the licensee's radiation protection program (RPP). Typically, the reference level is less than the action level in the licensee's RPP.

Reference levels may be used for interpreting workplace or bioassay monitoring data and to signal potential intakes. Applicable to routine and special bioassay monitoring programs, these levels allow a graded response to potential intakes and therefore are not intended to be a regulatory limit per se. Reference levels are typically expressed as fractions of the ALI. The sum of ratios (intake over ALI) should be used when more than one radionuclide is involved.

Because bioassay monitoring programs rarely measure intake, derived reference levels-expressed in terms of the quantity that is measured-are generally a more useful quantity. A derived reference level is the bioassay-determined activity due to occupational sources. The derived reference level for a particular bioassay measurement is expressed in the same units as the bioassay measurement results. For routine bioassay programs, reference levels should be based on an assumption of intake at the mid-point in the monitoring period.

For some radionuclides and types of bioassay, non-occupational sources may cause typical results to exceed the analytical decision level and a derived reference level. If bioassay results normally or often exceed a derived reference level due to non-occupational sources, the derived reference level may be increased if expected bioassay results due to non-occupational sources are known (a study using a control group with similar non-occupational exposure but no potential for occupational exposure may be used for this purpose). The adjusted derived reference level is set no higher than the 99 percentile of the control group [2]. If non-occupational levels exceed the Derived Investigation Level (DIL), then alternate methods of intake monitoring should be used if possible.

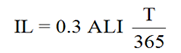

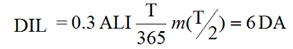

The reference levels used in this report are the DA, the Investigation Level (IL), and the DIL. The DA is defined in Section 3.2, Determining Frequency. The IL and DIL are defined below.

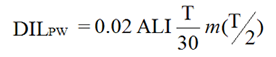

where:

- T

- = the monitoring period, in days

-

m(

)

)

- = the fraction of the intake that is retained in a tissue, organ or the whole body, or excreted from the body, at the mid-point in the monitoring period; a function of time with units of "Bq per Bq of intake" for in vivo bioassay, and Bq/L per Bq of intake for in vitro bioassay

An example of a DIL table for 137Cs inhalation of type F compounds is given in Appendix B, Examples, Table B2.

To account for the reduced dose limit for pregnant workers, a DIL for pregnant workers should be established. The duration of a pregnancy is usually 37 to 42 weeks (or between 9 and 10 months), and the pregnant worker dose limit is 4 mSv for the balance of the pregnancy (that is, from the time the worker informs the licensee). Given conservative assumptions (for example, that the pregnancy is declared immediately), then ensuring that the pregnant worker's dose is < 0.4 mSv per month helps to ensure the 4 mSv limit is not exceeded. Consequently, a DIL for pregnant workers, DILPW, may be set as:

4.2 Putting Bioassay Results in Perspective

Bioassay results may be interpreted by comparison with derived reference levels. Table 3 provides suggested reference levels that may form the basis for interpreting bioassay results and for taking appropriate actions.

| Bioassay Result | Recommended Response |

|---|---|

| < DA | Record the bioassay measurement result. |

| DA ≤ result < DIL | Confirm and record the bioassay measurement result. If the result is confirmed, assess the CED. |

| ≥ DIL | Confirm and record the bioassay measurement result. If the result is confirmed, assess the CED. Investigate to find and correct the cause of the intake. |

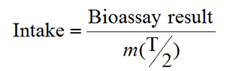

To assess the CED, the bioassay results should first be combined with m(

) to estimate the intake:

) to estimate the intake:

The CED can then be estimated by setting:

CED = Intake × e(50)

where e(50) (measured in Sv/Bq) is the dose per unit intake for the radionuclide, particle size and chemical form of interest [14]. If more than about 10% of the actual measured quantity may be attributed to intakes in previous intervals, for which intake and dose have already been assessed, a correction should be made [7].

4.3 Accuracy of Bioassay Results

Many components contribute to the overall accuracy of a dose estimate. These include the accuracy of:

- The detector system;

- The measurement methodology;

- The biological model used to relate the observable internal radioactivity to the radiation dose received; and

- The uncertainty of the actual time of internalization of the radioactivity relative to the time of the bioassay measurement.

This section deals only with the accuracy of components 1 and 2. All aspects of the biological model uncertainty, which sometimes may be the predominant source of inaccuracy and uncertainty in the final dose estimation, are detailed in Reliability of the ICRP's Systemic Biokinetic Models, Radiation Protection Dosimetry, Vol. 79, R.W. Leggett [15]. Uncertainties related to the time of intake with respect to the time at which the monitoring is performed are discussed briefly in Section 3.2, Determining Frequency.

In designing and setting up any bioassay monitoring program, it is important to consider the accuracy of the instrumentation relative to the measurement that has to be made. The complete measurement system should be such that any error in the final measurement would have a minor influence on the overall accuracy of the estimated radiation dose received by the worker. As some of the other uncertainties (i.e., items 3 and 4, above) can be significant, it is considered adequate that the detection instrument component of the uncertainty lies within the range -25% to +50% [16].

The following considerations should be included in the evaluation of detection instrument accuracy and measurement methodology:

-

The net statistical counting error.

This includes the statistical error in the bioassay count and the statistical error in the measurement of the background count rate. The background count rate measured should be appropriate for the standard, sample or subject. -

The error caused by variations in counting geometry.

This should include allowances for physical variations in the subjects or samples being counted, particularly as related to the specific counting equipment being used. -

The error introduced by the attenuation of the emitted radiation by overlying tissue during in vivo counting.

The effect of overlying tissue should be considered where the gamma emission of a nuclide in question is less

than 200 keV [7], or where Bremsstrahlung from beta emissions are being counted.

This requires the estimation of the average depth and density of the overlying tissue, which may vary significantly from one individual to another. -

The instrument calibration with respect to the isotope being measured in a geometry that is relevant to the

actual measurement.

The response of the bioassay instrument should be calibrated with respect to the isotope of interest and a regular quality control program should be in place to ensure that this calibration is constantly maintained. Frequent internal checks using a long-lived radioactive source should be performed on a regular basis to confirm that the detector response is constant over time and that the instrument is functioning properly [16].

Appendix B, Examples, Example 2 provides a sample calculation of counting error on a bioassay result.

5.0 Recording Bioassay Results

A record of bioassay results enables dose data to be traced for future dose reconstructions.

To comply with section 27 of the NSCA, section 28 of the General Nuclear Safety and Control Regulations, and subsection 5(1) and section 24 of the Radiation Protection Regulations, a bioassay record shall be kept for each individual participating in the bioassay program, and this record shall clearly identify the employee by name and job category. Additional information may be required to comply with licence conditions. For each dosimetry period, the bioassay data should be kept, as well as the date the measurement was taken. Records should also include instrument quality control, calibration results, and records of traceability to primary or secondary laboratories. [16]

Appendix A: Selecting Participants in a Routine Program Based on Activity Handled

Guidance on selecting participants in a routine bioassay program on the basis of the activity handled or the activity in process can be found in various references [2, 5, 17]. The values in Table 1 have been mainly based on the approach in American National Standard-Design of Internal Dosimetry Programs, Health Physics Society; however, similar values may be obtained using other references.

Potential Intake Fraction (PIF)

The potential intake fraction (PIF) is defined as:

PIF = 10-6 × R × C × D × O × S

where:

- 10-6

- = Brodsky's factor [18]

- R

- = release factor

- C

- = confinement factor

- D

- = dispersibility factor

- O

- = occupancy factor

- S

- = special form factor

Release Factor (R)

| Gases, strongly volatile liquids | 1.0 |

| Non-volatile powders, somewhat volatile liquids | 0.1 |

| Liquids, general, large area contamination | 0.01 |

| Solids, spotty contamination, material trapped on large particles; e.g., resins | 0.001 |

| Encapsulated material | 0 |

Confinement Factor (C)

| Glove box or hot cell | 0.01 |

| Enhanced fume hood (enclosed with open ports for arms) | 0.1 |

| Fume hood | 1.0 |

| Bagged or wrapped contaminated material, bagged material in wooden/ cardboard boxes, greenhouses | 10 |

| Open bench-top, surface contamination in a room with normal ventilation | 100 |

Dispersibility Factor (D)

| Actions that add energy to the material (heating, cutting, grinding, milling, welding, pressurizing, exothermic reactions) | 10 |

| Other actions (that do not enhance dispersibility) | 1 |

Occupancy Factor (O)

| Annual or one-time use | 1 |

| Monthly use or few times per year | 10 |

| Weekly, tens of times per year or tens of days for a one-time project | 50 |

| Essentially daily use | 250 |

Special Form Factor (S)

| DNA precursors (except 32P, 35S, or 131I) | 10 |

| Other material | 1 |

Values in Table 1

| Gases and volatile liquids |

R = 1 (Gases, strongly volatile liquids) D = 1 (No energy added to system) O = 250 (Essentially daily use) S = 1 |

| Powders |

R = 0.1 D = 1 (No energy added to system) O = 250 (Essentially daily use) S = 1 |

| Non-volatile liquids and solids |

R = 0.01 (liquids, large area contamination) D = 1 (No energy added to system) O = 250 (Essentially daily use) S = 1 |

Appendix B: Examples

B.1 Example 1: Determining Participation in a Bioassay Program

A worker handles on average:

- 1 × 106 Bq of 125I, three times per week, under a fume hood (assuming that ingestion is the most-likely route of intake),

- 1 × 107 Bq of 3H (as tritiated water), almost daily under a fume hood (assuming ingestion), and

- 0.6 × 106 Bq of 131I, four times per year on a bench top (assuming inhalation).

All of the radioactive materials are in a relatively volatile form.

The following information should be determined:

- Total intake per year,

- Dose conversion coefficient (this example uses a dose conversion coefficient of e(50), from ICRP Publication 68 [14]),

- Annual Limit on Intake (ALI),

- Potential Intake Fraction (PIF); see Appendix A,

- Coefficients rj, where j = A, B, and C (corresponding to the three radionuclide intakes defined above), and

- Sum coefficient Rj, where Rj =rA + rB + rC.

Table B1 provides step-by-step sample calculations to determine the values of rj and Rj.

In this example, the results of the calculations in Table B1 are:

- Rj < 1, therefore (according to Section 4.2, Putting Bioassay Results In Perspective), the worker need not be subject to bioassay monitoring.

- However, rA = 0.38 > 0.3, so the licensee may choose to monitor the worker for 125I.

Table B1: Evaluation of coefficients rj and sum coefficient Rj

| 125I (ingestion) | 3H (ingestion) | 131I (inhalation) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intake | 1 MBq per session | 10 MBq per session | 0.6 MBq per session |

| Total intake per year |

106 × (3 × 52) = 0.16 GBq/year |

107 × (5 × 52) = 2.6 GBq/year |

0.6 × 106 × 4 = 2.4 MBq/year |

|

Dose Conversion Coefficient e(50) (refer to ICRP-68) |

1.5 × 10-8 Sv/Bq | 1.8 × 10-11 Sv/Bq | 2.0 × 10-8 Sv/Bq |

Annual Limit on Intake (ALI), where:

|

1.3 MBq/year | 1.1 GBq/year | 1.0 MBq/year |

|

Potential Intake Fraction (PIF) (see Appendix A) |

Occupancy factor = 3 × 52 |

Occupancy factor = 250 Confinement factor = 1 PIF = 2.5 × 10-4 |

Occupancy factor = 4 Confinement factor = 100 PIF = 4 × 10-4 |

Ratios rj, where:

|

|

|

|

| Sum of ratios, rj |

|

||

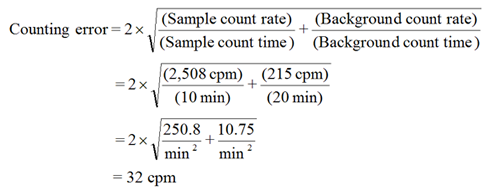

B.2 Example 2: Determining the Counting Error (Uncertainty)

The steps to calculate the error resulting from the detector system (counting statistics), and a demonstration of how the counting error is calculated from a single bioassay result, are shown below:

(a) Direct measurement results:

- Sample count:

- 25,077 (per litre of urine)

- Sample count time:

- 10 minutes

- Background count:

- 4,300 (per litre of urine)

- Background count time:

- 20 minutes

From these data, the count rates are calculated as follows:

- Sample count rate

- = (Sample count) / (Sample count time)

- = 25,077/10 min.

- = 2,508 counts per minute (cpm)

Similarly, the background count rate is calculated as follows:

- Background count rate

- = (Background count) / (Background count time)

- = 4,300/20 min.

- = 215 cpm

(b) Net count rate:

The background count rate is subtracted from the sample count rate to obtain the net count rate:

2,508 - 215 = 2,293 cpm.

(c) Counting error estimation: [19]

The counting error (at the 95% confidence interval based only on counting statistics) is then:

Therefore the sample count rate is 2,293 ± 32 cpm. The statistical error of 32 cpm represents a relative error of (32 cpm) / (2,293 cpm) = 1.4 %.

(d) Result of measurements and analysis:

If the detector efficiency for 137Cs is 10%, the number of disintegrations per minute (dpm) is:

(net count rate) / (efficiency) = 2,293/0.10 = 22,930 dpm.

To express this result as disintegrations per second, or becquerels (Bq), divide by 60 to obtain 382 Bq. The relative error of 1.4% is carried over to the activity:

382 Bq × 1.4% = 5 Bq.

The bioassay sample result, including the statistical error only, therefore is:

(382 ± 5 Bq/L) × (1.6 L/day) = 611 ± 8 Bq/day, assuming 1.6 L of a daily urine yield for a Reference Man [20]

(e) Conclusion

This example represents accounting for only one uncertainly; i.e., counting statistics. Other factors, such as counting geometry or calibration error, may increase the uncertainty.

B.3 Example 3: Determining the Monitoring Frequency for Intakes of 137Cs

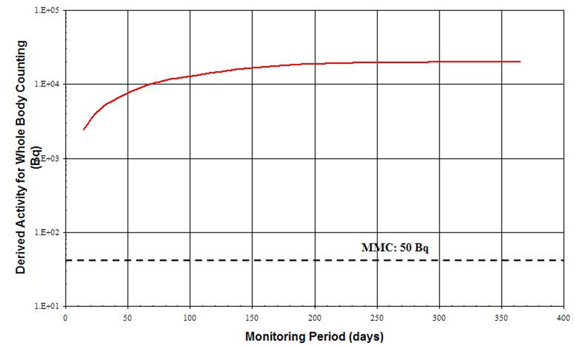

Table 2 in Section 3.1, Methods of Bioassay, illustrates that both whole body counting and urine analysis (gamma counting) are appropriate for detecting 137Cs. The monitoring period for whole body counting is considered first.

Derived Activity (DA) is the measurable activity that indicates the dose of 1 mSv or more of the committed effective dose. This threshold must be determined in a reliable manner; that is, the DA must lie above the Minimum Measurable Concentration (MMC) level. If it is below, the measured concentration becomes irrelevant. DA depends on the time span between monitoring measurements (monitoring period). In this example, the case of 137Cs inhalation intake is examined.

In vivo bioassay:

Figure B1 represents the DA as a function of the Monitoring Period. The detection limit (MMC) has been superimposed onto the plot. This figure illustrates that DA stays above the MMC over a wide range of monitoring periods. Any period up to one year could therefore be a reasonable interval between taking a bioassay for monitoring purposes. To determine the optimum monitoring period, other considerations described in Section 3.2, Determining Frequency, should be taken into account.

Figure B1: Acute Inhalation of 137Cs, type F, whole body bioassay. Derived Activity as a function of the Monitoring Period (time-span between measurements)

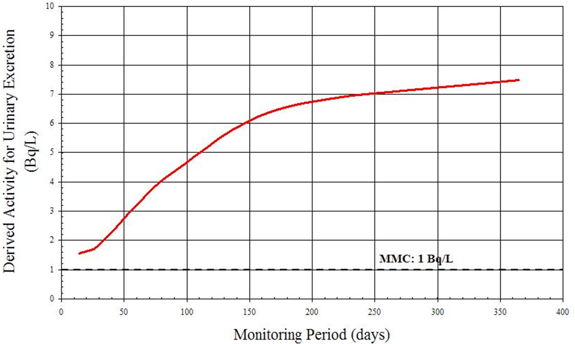

In vitro bioassay:

Figure B2 represents DA as a function of monitoring periods. The curve is obtained by applying definitions given in Section 3.2, Determining Frequency. The DA is compared to the MMC. The DA curve stays well above the horizontal line representing the MMC at 1 Bq/L through the tabulated period [7] ranging from 7 days to 1 year. Selection of a specific monitoring period will involve other factors, described in Section 3.2.

Figure B2: Acute Inhalation of 137Cs, type F, in vitro bioassay (urinary excretion). Derived Activity as a function of the Monitoring Period (time span between measurements).

B.4 Example 4: Determining the Monitoring Frequency for Intakes of 131I

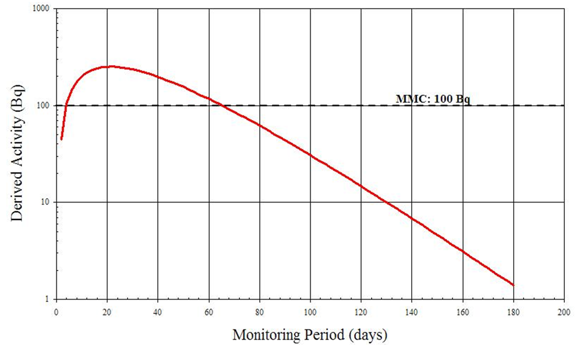

An achievable MMC of 100 Bq for thyroid monitoring for 131I has been suggested [7]. As in the previous example, DA is plotted against various monitoring periods from 2 to 180 days. The result is illustrated in Figure B3.

From the graph it is clear that if the monitoring period is less than 4 days or greater than 65 days, the 131I activity in the thyroid is inferior to the MMC and thus is not detected. In this case, a period of 14 or 30 days is an optimal time frame for monitoring.

Figure B3: 131I in the Thyroid (Acute Vapour Inhalation) Derived Activity as Function of Time

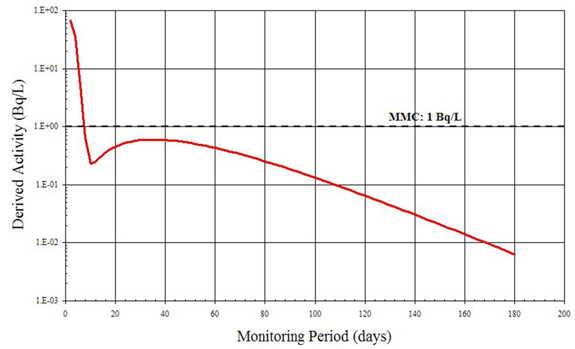

Although 131I can be detected by in vitro measurements, Figure B4 suggests that after 5 days the quantity of 131I being excreted is inferior to the MMC of 1 Bq/L [7]. In addition, an individual's rate of radioiodine excretion depends on many factors including diet, age and the use of medications. The individual variation in excretion rate is likely great and therefore a 5 day monitoring period may not always allow the detection of 1 DA. In this case, urinalysis is not a recommended routine monitoring method for assessing intakes of 131I.

Figure B4: Derived Activity for Urinary Excretion of 131I Following Acute Vapour Inhalation

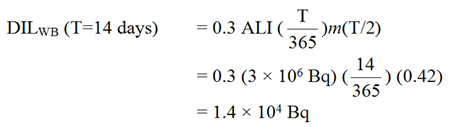

B5 Example 5: Derived Investigation Levels for 137Cs Inhalation

The Derived Investigation Levels (DILs) for inhalation of Type F 137Cs whole-body activity and urinary excretion are calculated using values of m(T/2) taken from Individual Monitoring for Internal Exposure of Workers, Replacement of ICRP Publication 54, International Commission on Radiological Protection, Publication 78 [7]. For whole body retention, 14-day routine monitoring period, the parameters are:

- Monitoring period:

- T = 14 days

- Whole body retention at T/2:

- m(7 days) = 0.42

- ALI

- = 3 × 106 Bq[14]

Whole-body and urinary excretion DIL values for routine monitoring periods varying from 14 to 180 days are shown in Table B2. The values apply to inhalation of Type F 137Cs.

Table B2: Derived Investigation Levels for Routine Monitoring of 137Cs

| Monitoring Interval(days) | DIL: Whole Body Activity (Bq) | DIL: Daily Urinary Excretion (Bq/day) | DIL: Urinary Excretion (Bq/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 1.4 × 104 | 1.3 × 102 | 9.1 × 101 |

| 30 | 2.9 × 104 | 1.6 × 102 | 1.1 × 102 |

| 60 | 5.4 × 104 | 2.7 × 102 | 1.9 × 102 |

| 90 | 7.3 × 104 | 3.7 × 102 | 2.6 × 102 |

| 180 | 1.1 × 105 | 5.5 × 102 | 3.9 × 102 |

Glossary

- Absorbed dose (D)

- The energy absorbed through exposure to radiation per unit mass. The SI unit for D is gray (Gy).

- Analytical decision level

- The amount of a count or final instrument measurement of a quantity of analyte at or above which a decision is made that a positive quantity of the analyte is present; measured in Bq/L.

- Annual limit on intake (ALI)

- The activity of a radionuclide that, when taken into the body, results in a CED of 20 mSv.

- Bioassay

- Measurement of the amount or concentration of a radionuclide in the body or in biological material excreted or removed from the body and analyzed for purposes of estimating the quantity of radionuclide in the body.

- Biological half-life

- The time required for a biological system, such as a person, to eliminate by natural processes (other than radioactive decay) one-half of the amount of a substance, such as a radionuclide, that has entered it.

- Biokinetic model

- A mathematical description of the behaviour of radionuclides in the metabolic processes of cells, tissues, organs and organisms. It is most frequently used to describe distribution of radionuclides among tissues and excretion.

- Bremsstrahlung

- Electromagnetic radiation produced by the deceleration of a charged particle, such as an electron, when deflected (change of momentum) by another charged particle, such as an atomic nucleus.

- Committed effective dose (CED) (e(50))

- The effective dose resulting from intake of a radioactive substance. The dose is accumulated over a period of 50 years after initial intake. The SI unit for CED is the sievert (Sv).

- Derived activity (DA)

- The expected retention or excretion rate, either expressed as Bq or Bq/d, from a single measurement of a radionuclide made at the end of a monitoring period, such that the corresponding extrapolated annual committed effective dose is equal to 1 mSv. The DA is calculated assuming the intake occurs at the mid-point in the monitoring period.

- Derived air concentration (DAC)

- The concentration of a radionuclide in air that, when inhaled at a breathing rate of 1.5 m3 per hour for 2,000 hours per year, results in the intake of 1 ALI.

- Derived investigational level (DIL)

- When a program of monitoring for internal contamination is in place, it is usual to determine, ahead of time, levels of contamination above which certain actions are initiated. The derived investigational level (DIL) is the level that triggers an investigation and dose assessment, measured in Bq.

- Derived reference level

- Bioassay-determined activity due to occupational sources, measured in Bq/L.

- Effective dose (E)

- The sum of the products, in sievert, obtained by multiplying the equivalent dose of radiation received by and committed to each organ or tissue set out in column 1 of an item of Schedule 1 (Radiation Protection Regulations) by the tissue weighting factor set out in column 2 (Radiation Protection Regulations) of that item.

- Equivalent dose (HT)

- The product, in sievert, obtained by multiplying the absorbed dose of radiation of the type set out in column 1 of an item of Schedule 2 (Radiation Protection Regulations) by the radiation weighting factor set out in column 2 (Radiation Protection Regulations) of that item.

- Excretion function (m)

- A mathematical expression for the fractional excretion of a radionuclide from the body at any time following intake, generally expressed as becquerels excreted per day, per becquerel taken in.

- Intake

- The amount of a radionuclide, measured in Bq, taken into the body by inhalation, absorption through the skin, injection, ingestion, or through wounds.

- Investigational level (IL)

- An indicator of intake (in Bq) of radioactive substance that requires special monitoring of the worker; typically expressed as a fraction of ALI.

- In vitro bioassay

- Measurements to determine the presence of, or to estimate the amount of, radioactive material in excreta or other biological materials excreted or removed from the body.

- In vivo bioassay

- Measurements of radioactive material in the body using instruments that detect radiation emitted from the radioactive material in the body.

- Minimum measurable concentration (MMC)

- The smallest amount (activity or mass) of a radionuclide (or analyte) in a sample that will be detected with a probability of non-detection (Type II error) while accepting a probability of erroneously deciding that a positive (non-zero) quantity of analyte is present in an appropriate blank (Type I error); measured in Bq/L.

- Nuclear energy worker (NEW)

- A person who is required, in the course of the person's business or occupation in connection with a nuclear substance or nuclear facility, to perform duties in such circumstances that there is a reasonable probability that the person may receive a dose of radiation that is greater than the prescribed limit for the general public.

- Personal air sampler (PAS)

- An air sampler, consisting of a filter holder and battery-powered vacuum pump, worn by a worker to estimate breathing zone concentrations of radionuclides. Personal air samplers are also called lapel samplers.

- Potential intake fraction (PIF)

- A dimensionless quantity that defines intake as a fraction of exposure to contamination. A function of several factors: release, confinement, dispersability, occupancy. For example, PIF=0 for encapsulated material, as no intake of radioactive nuclear substances into a worker's body can occur.

- Radiation weighting factor

- The factor by which the absorbed dose is weighted for the purpose of determining the equivalent dose. The radiation weighting factor for a specified type and energy of radiation has been selected to be representative of values of the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of that radiation in inducing stochastic effects at low doses. The RBE of one radiation compared with another is the inverse ratio of the absorbed doses producing the same degree of a defined biological end point [21].

- Sievert (Sv)

- Unit of equivalent dose, effective dose, and CED. One sievert is defined as one joule of energy absorbed per kilogram of tissue multiplied by an appropriate, dimensionless, weighting factor. See also "equivalent dose" and "effective dose".

- Tissue weighting factor

- The factor by which the equivalent dose is weighted for the purpose of determining the effective dose. The tissue weighting factor for an organ or tissue represents the relative contribution of that organ or tissue to the total detriment due to effects resulting from uniform irradiation of the whole body [21].

- Workplace air sampler (WPAS)

- An air sampler, consisting of a filter holder and vacuum pump, mounted in a working area to estimate breathing zone concentrations of radionuclides.

References

- U.S. Department of Energy, DOE Standard Internal Dosimetry, DOE-Std-1121-98, 1999.

- Health Physics Society, American National Standard-Design of Internal Dosimetry Programs, ANSI/HPS N13.39-2001.

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), Ascertaining and Recording Radiation Doses to Individuals, Regulatory Guide G-91, 2003(a).

- CNSC, Designing and Implementing a Radiobioassay Program, Report of the CNSC Working Group on Internal Dosimetry, RSP-0182A.

- International Atomic Energy Agency, Assessment of Occupational Exposures Due to Intakes of Radionuclides, Safety Guide RS-G-1.2, 1999.

- CNSC, Radiobioassay Protocols for Responding to Abnormal Intakes of Radionuclides, Regulatory Guide G-147, 2003(b).

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), Individual Monitoring for Internal Exposure of Workers, Replacement of ICRP Publication 54, Publication 78, Pergamon Press, 1997.

- ISO 20553:2006, Radiation protection—Monitoring of workers occupationally exposed to a risk of internal contamination with radioactive material.

- ICRP, Human Respiratory Tract Model for Radiological Protection, Publication 66, Vol. 24, No. 1-3, Pergamon Press, 1994.

- Health Physics Society, American National Standard-Performance Criteria for Radiobioassay, HPS N13.30-1996.

- CNSC, Uranium Intake-Dose Estimation Methods, Report of the CNSC Working Group on Internal Dosimetry, RSP-0165, 2003(c).

- ICRP, Individual Monitoring for Intakes of Radionuclides by Workers: Design and Interpretation, Publication 54, 1989.

- Health and Welfare Canada, Bioassay Guideline 4—Guidelines for Uranium Bioassay, 88-EHD-139, 1987.

- ICRP, Dose Coefficients for Intakes of Radionuclides by Workers, Publication 68, Vol. 24, No. 4, Pergamon Press, 1994.

- Leggett, R.W., Reliability of the ICRP's Systemic Biokinetic Models, Radiation Protection Dosimetry, Vol. 79, 1998.

- CNSC, Technical and Quality Assurance Requirements for Dosimetry Services, S-106 rev 1, 2006.

- Hickey, E.E., Stoetzel, G.A., McGuire, S.A., Strom, D.J., Cicotte, G.R., Wiblin, C.M., Air Sampling in the Workplace, NUREG-1400, 1993.

- Brodsky, A., Resuspension Factors and Probabilities of Intake of Material in Process (or is 10-6 a magic number in health physics?), Health Physics, Vol. 39, No. 6, pp. 992-1000, 1980.

- Knoll, G.F., Radiation Detection and Measurement, John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

- ICRP, Basic Anatomical and Physiological Data for Use in Radiological Protection: Reference Values, Publication 89, 2003.

- ICRP, 1990 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection, Vol. 21, No. 1-3, Publication 60, 1991.

Additional Information

The following documents contain additional information that may be of interest to persons involved in designing and implementing a bioassay program:

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), RD-58 Thyroid Screening for Radioiodine, July 2008.

- Health and Welfare Canada, Bioassay Guideline 1-General Guidelines for Bioassay Programs, Environmental Health Directorate, 81-EHD-56, 1980.

- Health and Welfare Canada, Bioassay Guideline 2—Guidelines for Tritium Bioassay, Report of the Working Group on Bioassay and in vivo Monitoring Criteria, Environmental Health Directorate, 83-EHD-87, 1983.

- Leggett, R.W., Predicting the Retention of Cs in Individuals, Health Physics, Vol. 50, pp. 747-759, 1986.

- Strom, D.J., Programmes for Assessment of Dose from Intakes of Radioactive Materials, Internal Radiation Dosimetry, Health Physics 1994 Summer School, pp. 543-570, 1994.

- ICRP, Report of the Task Group on Reference Man, Publication 23, 1975.

Page details

- Date modified: