Environmental Protection Review Report – Darlington Nuclear Generating Station

Executive summary

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) conducts environmental protection reviews (EPRs) for all nuclear facilities with potential interactions with the environment, in accordance with its mandate under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) to ensure the protection of the environment and the health and safety of persons. An EPR is a science-based environmental technical assessment conducted by CNSC staff. The fulfillment of other regulatory compliance oversight of the CNSC’s mandate is met through other oversight activities.

This EPR report was written by CNSC staff as a stand-alone document, describing the scientific and evidence-based findings from CNSC staff’s review of Ontario Power Generation’s (OPG’s) environmental protection measures. The periodic EPR report provides an assessment of documents related to the Darlington Nuclear Site (DN site), which consists of the Darlington Nuclear Generating Station (DNGS) and the Darlington Waste Management Facility (DWMF).

The DN site is located within the lands and waters of the Michi Saagiig Anishinaabeg, the Gunshot Treaty (1787-88), the Williams Treaties (1923), and the Williams Treaties First Nations Settlement Agreement (2018). Under its current power reactor operating licence, PROL 13.01/2025, OPG is permitted to operate the DNGS units for power production. Under the waste facility operating licence, WFOL-W4-355.00/2033, OPG is also permitted to operate the DWMF. This EPR does not encompass the proposed Darlington New Nuclear Project or the licences to prepare a site, the applications to modify the licence to prepare a site or the application for a licence to construct.

CNSC staff’s EPR report focuses on items that are of Indigenous, public, and regulatory interest, such as potential environmental releases from normal operations, as well as the risk of releases of radiological nuclear and hazardous (non-radiological) substances to the receiving environment, valued ecosystem components (VECs) and species at risk. CNSC staff also endeavour to focus on items related to Indigenous Nations and communities Rights, values and culture, when information is shared with the CNSC.

This EPR report includes CNSC staff’s assessment of documents submitted by the licensee to CNSC staff from 2016 to 2023 and the results of CNSC staff’s compliance activities, including the following:

- engagement with Indigenous Nations and communities

- regulatory oversight activities

- the results of OPG’s environmental monitoring, as reported in the environmental monitoring program reports

- OPG’s 2020 environmental risk assessment for the DN site

- OPG’s 2021 preliminary decommissioning plan for the DN site

- the results of the CNSC’s Independent Environmental Monitoring Program

- the results from other environmental and groundwater monitoring programs and/or health studies (including studies completed by other levels of government) in proximity to the DN site

Based on their assessment and evaluation of OPG’s documentation and data, CNSC staff have found that the potential risks from nuclear and hazardous releases to the atmospheric, terrestrial, aquatic and human environments from the DN site are low to negligible, and that any releases are at levels similar to natural background. Furthermore, human health is not impacted by operations at the DN site and the health outcomes are indistinguishable from health outcomes found in the general public. CNSC staff have also found that OPG continues to implement and maintain effective environmental protection measures that meet regulatory requirements and adequately protect the environment and the health and safety of persons. CNSC staff will continue to verify OPG’s environmental protection programs through ongoing licensing and compliance activities.

CNSC staff’s findings from this report may inform recommendations to the Commission in future licensing and regulatory decisions, as well as inform CNSC staff’s ongoing and future compliance verification activities. CNSC staff’s findings do not represent the Commission’s conclusions. The Commission’s decision-making will be informed by submissions from CNSC staff, the licensee, Indigenous Nations and communities, and the public, as well as through any interventions made during public hearings on Commission proceedings.

A pamphlet of this EPR report with a public friendly summary is available in Appendix A of this report. OPG also makes many summary documents, including reports containing environmental data, available on OPG’s website. References used throughout this document are available upon request and requests can be sent to er-ee@cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Purpose

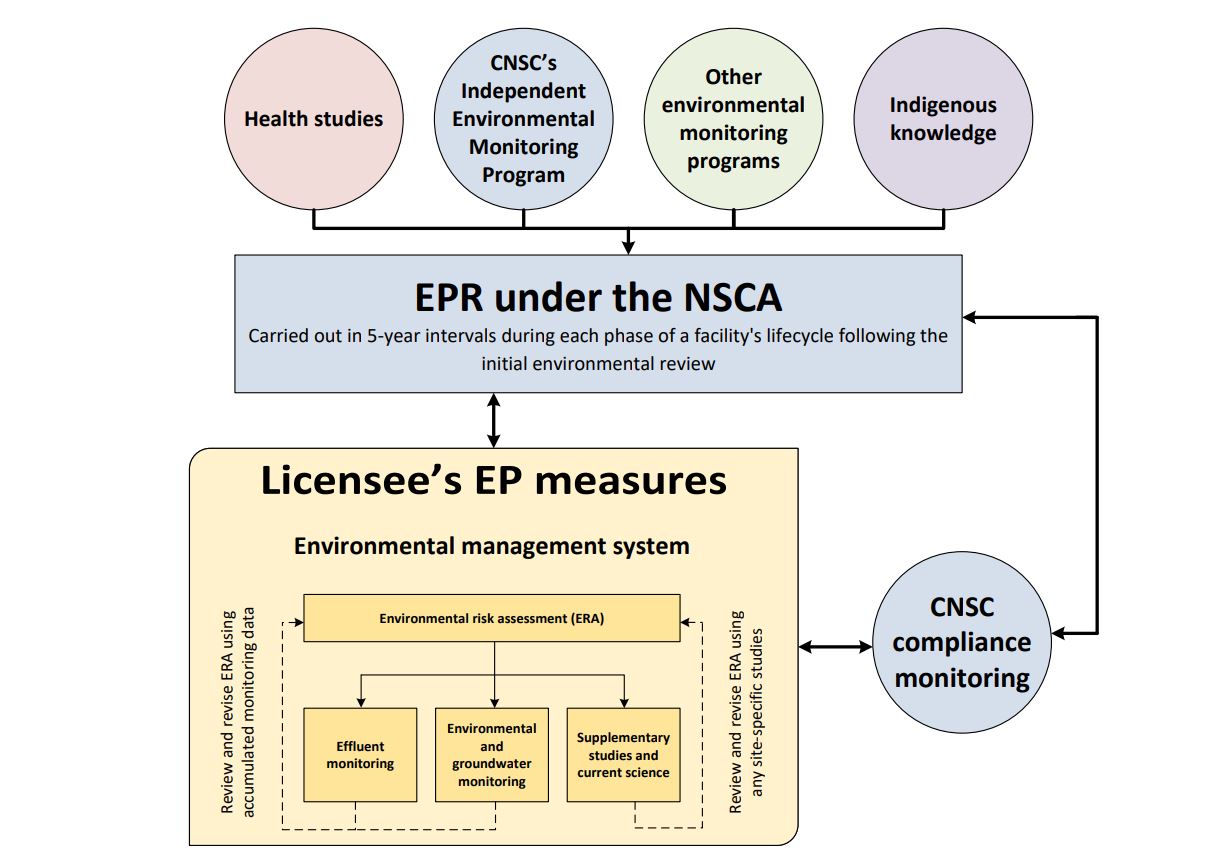

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) conducts environmental protection reviews (EPRs) for all nuclear facilities with potential interactions with the environment, in accordance with its mandate under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) Footnote 1. CNSC staff assess the environmental and health effects of nuclear facilities and/or activities during every phase of a facility’s lifecycle. As shown in figure 1.1, an EPR is a science-based environmental technical assessment conducted by CNSC staff to support the CNSC’s mandate for the protection of the environment and human health and safety, as set out in the NSCA. The fulfillment of other aspects of the CNSC’s mandate is met through other regulatory oversight activities and is outside the scope of this report. Each EPR report is typically conducted every 5 years and is informed by the licensee’s environmental protection (EP) program and documentation submitted by the licensee as per regulatory reporting requirements.

As per the CNSC’s Indigenous Knowledge Policy Framework Footnote 2, the CNSC recognizes the importance of considering and including Indigenous Knowledge in all aspects of its regulatory processes, including EPRs. CNSC staff are committed to working directly with Indigenous Nations and communities and knowledge holders on integrating their knowledge, values, land use information, and perspectives in the CNSC’s EPR reports, where appropriate and when shared with the licensee and the CNSC.

The purpose of this EPR is to report the outcome of CNSC staff’s assessment of the Ontario Power Generation Inc. (OPG)’s EP measures and CNSC staff’s health science and environmental compliance activities for the Darlington Nuclear Site (DN site) – operations at both the Darlington Nuclear Generating Station (DNGS) and the Darlington Waste Management Facility (DWMF). This review serves to assess whether OPG’s EP measures at the DN site meet regulatory requirements and adequately protects the environment and health and safety of persons.

While this EPR focuses on the EP measures of the DN site from 2016-2023, it should be noted that in May 2024, OPG submitted a licence application to renew the power reactor operating licence from December 1, 2025 to November 30, 2055 Footnote 3. CNSC staff has prepared this EPR to inform the licensing decision of the Commission.

CNSC staff’s findings may inform recommendations to the Commission in future licensing and regulatory decision making, as well as inform CNSC staff’s ongoing and future compliance verification activities.

CNSC staff’s findings do not represent the Commission’s conclusions. The Commission is an independent, quasi-judicial administrative tribunal and court of record. The Commission’s conclusions and decisions are informed by information submitted by the applicant or licensee, the CNSC staff, Indigenous Nations and communities, and the public, as well as through any interventions made during public hearings on Commission proceedings.

EPR reports are prepared to thoroughly document CNSC staff’s technical assessment relating to a licensee’s EP measures and are posted online for information and transparency. Posting EPR reports online, separately from the documents drafted during the licensing process, allows interested Indigenous Nations and communities and members of the public additional time to review information related to EP prior to any licensing hearings or Commission decisions. CNSC staff may use the EPR reports as reference material when engaging with interested Indigenous Nations and communities, members of the public and interested stakeholders. To assist with outreach and engagement for the DN site, a pamphlet of this EPR report with a public friendly summary is available in Appendix A of this report.

This EPR report is informed by documentation and information submitted by OPG, compliance activities completed by CNSC staff from 2016 to 2023, and other sources, such as:

- engagement with Indigenous Nations and communities (section 1.2)

- regulatory oversight activities (section 2.0)

- CNSC staff’s review of OPG’s 2021 Nuclear Site preliminary decommissioning plan (PDP) Footnote 4 and the 2021 preliminary decommissioning plan for the Darlington Waste Management Facility Footnote 5 (section 2.2)

- CNSC staff’s review of OPG’s environmental and groundwater monitoring program results for Darlington from 2016 to 2023 Footnote 6 Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10 Footnote 11 Footnote 12 Footnote 13 Footnote 14 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 Footnote 17 Footnote 18 Footnote 19 Footnote 20

- data from studies related to assessments conducted for facilities and activities on the DN site (section 3.0)

- results of the CNSC’s Independent Environmental Monitoring Program (IEMP), including discussions with Indigenous Nations and communities (section 4.0)

- health studies with relevance to the DN site (section 5.0)

- data from other environmental monitoring programs (EMPs) in proximity to the DN site (section 6.0)

This EPR report focuses on topics related to the facilities’ environmental performance, including atmospheric (emission) and liquid (effluent) releases to the environment, and the potential transfer of constituents of potential concern (COPCs) through key environmental pathways and associated potential exposures and/or effects on valued ecosystem components (VECs), including human and non-human biota. VECs refer to environmental, biophysical or human features that may be impacted by a project. The value of a component relates not only to its role in the ecosystem, but also to the value people place on it (for example, it may have scientific, social, cultural, economic, historical, archaeological or aesthetic importance). The focus of this report is on radiological nuclear and hazardous substances associated with licensed activities undertaken at the DN site, with additional information provided on other topics of Indigenous, public and regulatory interest. CNSC staff also present information on relevant regional environmental and health monitoring, including studies conducted by the CNSC or other governmental organizations.

1.2 Facility overview

This section provides general information on the DN site, including a description of the site location and a basic history of site activities and licensing. This information is intended to provide context for later sections of this report, which discuss completed and ongoing environmental and associated regulatory oversight activities.

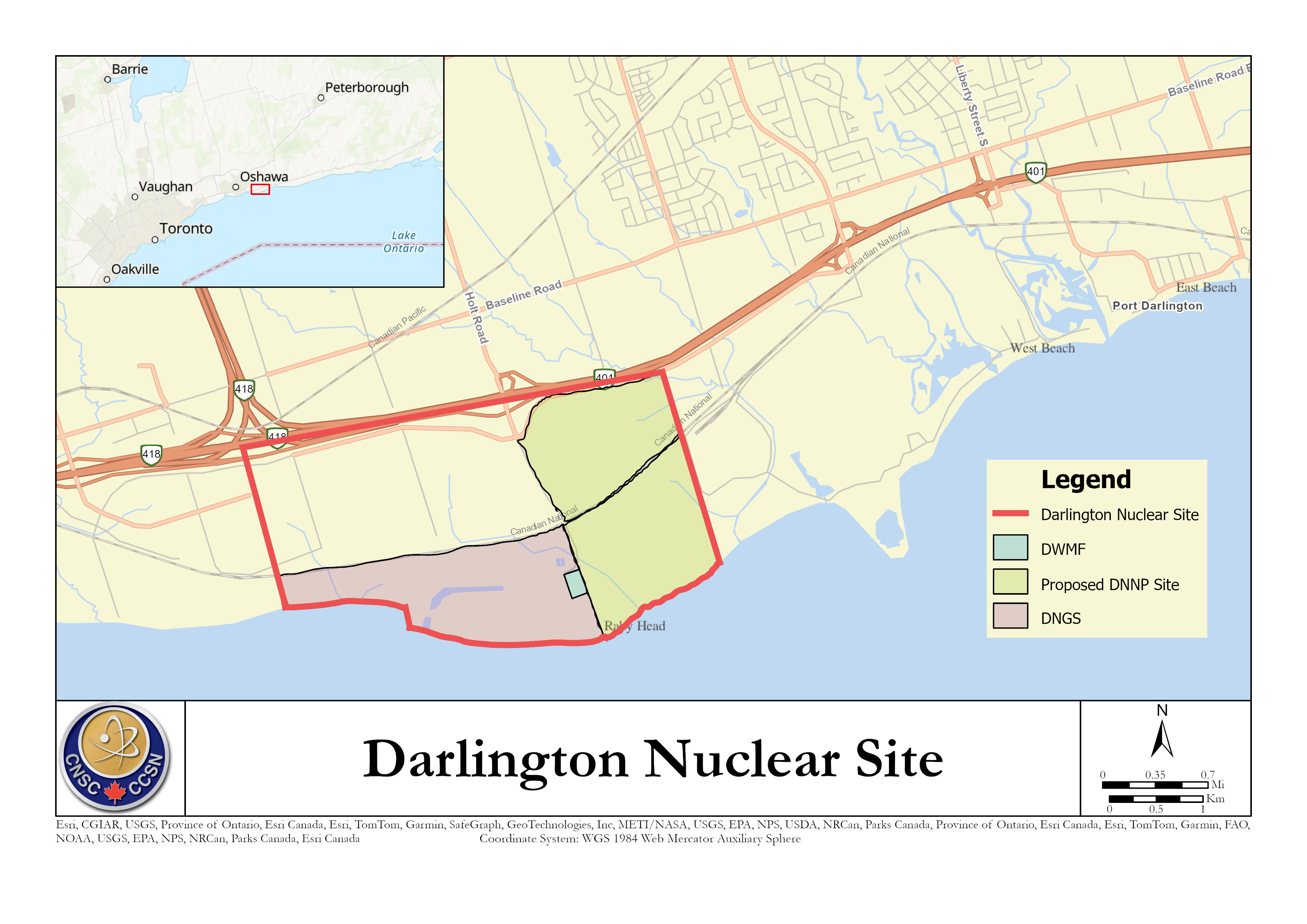

1.2.1 Site description

The DN is located within the lands and waters of the Michi Saagiig Anishinaabeg, the Gunshot Treaty (1787-88), the Williams Treaties (1923), and the Williams Treaties First Nations Settlement Agreement (2018). The facilities are located in the Municipality of Clarington, Ontario, (formerly the township of Darlington) on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The DN site is located approximately 5 kilometres (km) southwest of the community of Bowmanville, 10 km east-southeast of the City of Oshawa, and 70 km east of Toronto. The DN site is 485 hectares (ha) in area, with additional water lot areas extending into Lake Ontario to accommodate structures and features associated with the DNGS. The DN site lands are bounded by Highway 401 and Energy Drive West to the north and Lake Ontario to the south. To the west, the DN site is bounded by Solina Road and agricultural land. The St. Mary’s Cement Bowmanville plant occupies the land east of the DN site.

The DN site is owned and operated by the licensee, OPG. DNGS and the DWMF operate under separate licences issued by the Commission to OPG. This EPR Report includes CNSC staff’s assessment of the EP measures at both the DWMF and DNGS and does not encompass the proposed Darlington New Nuclear Project (DNNP) as this EPR report is meant to encompass the ongoing operations at the Darlington Nuclear site under the existing power reactor and waste facility operating licences.

The DN site houses the following nuclear facilities (figure 1.2):

- The DNGS, comprising 4 CANada Deuterium Uranium (CANDU) reactors and associated infrastructure and equipment

- The Tritium Removal Facility (TRF), where tritium is extracted from tritiated heavy water

- The DNNP lands

- The DWMF, located in a separate protected area to the east of the DNGS

The DN site also includes a visitor information centre, a Hydro One switching station (which connects DNGS to the Hydro One transmission corridor), technical and administrative support facilities and security facilities.

1.2.2 Facility operations

The DNGS began operating in 1990, and the DWMF became operational in 2008. Under the power reactor operating licence for the DNGS, OPG possesses and uses nuclear substances and associated equipment to generate power. Under the waste facility operating licence for the DWMF, OPG operates the waste management facility and associated activities to manage waste generated from the DNGS.

1.2.2.1 Darlington Nuclear Generating Station

The DNGS consists of 4 CANDU pressurized heavy water nuclear reactor units and auxiliary systems that support their operation and the production of electricity. As of the writing of this report, two reactor units are in operation (Units 2 and 3), and two reactor units (Units 1 and 4) are undergoing refurbishment and life extension.

The DN site comprises many buildings of various sizes with a wide range of functions (see figure 1.2). An overview of the main features is described in table 1.1.

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Reactor building | Reactor buildings contain 4 reactor vaults, a reactor auxiliary bay, steam generators and a containment envelope. The reactor vault contains the reactor core and assembly and the reactivity control devices. The reactor auxiliary bay contains the reactor auxiliary and secondary circuits for low temperature, pressure and radioactivity levels around each vault. The containment envelope encompasses the 4 reactor vaults, the fueling duct connected to each vault and a pressure relief duct which connects the fueling ducts to the vacuum building that condenses any releases of radioactive steam and prevents release outside of the station. |

| Primary Heat Transport and Generator Systems | The primary heat transport systems cool the reactor by circulating pressurized heavy water through the reactor fuel channels. The heat is transferred to light water through steam generators. |

| Powerhouse Building holding the Secondary Heat Transport and Turbine-Generator Systems | The Powerhouse holds four turbine halls, four auxiliary bays and a central service area as well as the secondary heat transport and turbine generator systems. The secondary heat transport system moves steam produced into the steam generators using heat from the primary heat transport system. This system rotates the turbines and attached generators to rotate and generate power. |

| Heavy Water Management Building | The heavy water management building comprises of the heavy water supply, collection and transfer, cleanup and upgrading and the vapour recovery and resin handling systems. This system circulates heavy water through the reactor vessel, separately from the primary heat transport system. |

| Tritium Removal Facility | The Tritium Removal Facility houses the processes which remove tritium from the heavy water. Once extracted, the tritium is stored in stainless steel containers within a concrete vault. |

| Fuelling Facilities Auxiliary Areas | The fuelling facilities auxiliary areas, which store new fuel and two irradiated fuel bays, are located at each end of the station. Irradiated fuel bays are used to store and cool used fuel bundles. The used fuel bundles are stored in these fuel bays for at least 10 years before transferring to the DWMF. |

| Forebay, intake channel and discharge channels | The intake channels draw condenser cooling water (CCW) from the forebay into each unit. After the CCW is used in the condensers, the CCW is discharged into Lake Ontario through the drainage channel. |

1.2.2.2 Darlington Waste Management Facility

The DWMF is located within its own fenced protected area and consists of 2 in-service storage buildings (each designed to house dry storage containers (DSCs)) and a DSC processing building. The DSC processing facility is used to prepare DSCs for storage. The used fuel Storage Buildings #1 and #2 provide interim site storage for the used fuel bundles of the DNGS until a disposal site for used fuel bundles becomes operational. Both DSC Storage Buildings #1 and #2 have the capacity to hold up to 500 DSCs, equivalent to roughly 9 years of operation for the DNGS.

The Retube Waste Storage Building (RWSB) stores intermediate-level wastes from the Darlington Refurbishment Project. The low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste that is produced from the DN site is transferred to the Western Waste Management Facility (WWMF) located on the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station site in Tiverton, Ontario.

Table 1.2 defines the key structural components of the DWMF.

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dry storage container | A free-standing reinforced concrete container with an inner steel liner and an outer steel shell that is designed and constructed to safely transfer and store dry used fuel on-site. |

| Processing building | A secured building where empty dry storage containers are prepared before being sent to the DNGS for used fuel loading, and where loaded dry storage containers are processed before being transferred to storage buildings. Processing activities include welding, painting and testing. The processing building also includes an amenities area with utility rooms, offices, washrooms, a lunch room and other supporting facilities. |

| Dry storage container transporter | A specially designed multi-wheeled vehicle for the transfer of dry storage containers between the DNGS’s irradiated fuel bays and the processing building, and from the processing building to storage buildings. |

| Retube Waste Storage Building | The retube waste storage building has the capacity to hold 490 dry storage modules containing intermediate level waste. |

2.0 Regulatory oversight

The CNSC regulates nuclear facilities and activities in Canada to protect the environment and the health and safety of persons in a manner that is consistent with applicable legislation and regulations, environmental policies and Canada’s international obligations. The CNSC assesses the effects of nuclear facilities and activities on human health and the environment during every phase of a facility’s lifecycle. This section of the EPR report discusses the CNSC’s regulatory oversight of OPG’s EP measures for the DN site.

To meet the CNSC’s regulatory requirements and according to the licensing basis for the DN site, OPG is responsible for implementing and maintaining EP measures that identify, control and (where necessary) monitor releases of nuclear and hazardous substances and their potential effects on human health and the environment. These EP measures must comply with, or have implementation plans in place to comply with, the regulatory requirements found in OPG’s licence and licence condition handbook (LCH). The relevant regulatory requirements for OPG’s DN site are outlined in this section of the report.

2.1 Environmental protection reviews and assessments

To date, 3 federal environmental assessments (EAs) and 2 EPRs (including this one) have been carried out for the DN site, as indicated in table 2.1. Subsection 2.1.1 provides a description of the EAs conducted under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA 1992) Footnote 21 predecessor to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012) Footnote 22. Subsection 2.1.3 provides information on the EPRs conducted for the DN site. In 2019, the Impact Assessment Act (IAA) Footnote 23 came into force, replacing CEAA 2012. OPG’s current activities at the DN site do not require an impact assessment under the IAA’s Physical Activities Regulations Footnote 24. The purpose of an assessment under any of these pieces of legislation is to identify the possible impacts of a proposed project or activity and to determine whether those effects can be adequately mitigated to protect the environment and the health and safety of persons.

| Project | Regime | EA start date | EA decision date | EA follow-up monitoring program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction of the Darlington Used Fuel Dry Storage Facility | CEAA 1992 | September 18, 2001 | November 7, 2003 | Completed |

| Darlington New Nuclear Project | CEAA 1992 | May 17, 2007 | May 8, 2012 April 22, 2024* |

Yes |

| Refurbishment and Continued Operation of DNGS | CEAA 1992 | June 24, 2011 | March 14, 2013 | Updated through the Integrated Implementation Plan |

*The CNSC Commission determined that the new technology proposed by OPG is not fundamentally different from the technologies assessed in the original EA and a new EA would not be required Footnote 25.

2.1.1 Environmental assessments completed under Canadian Environmental Assessment Act

Environmental assessments help guide the decision-making process. Historical and ongoing EAs as well as follow-up monitoring programs are reviewed by CNSC staff. CNSC staff acknowledge that these environmental assessments listed below occurred prior to the re-affirmation of the Williams Treaties First Nations harvesting Rights as part of the 2018 Williams Treaties First Nations Settlement Agreement. CNSC staff are committed to working with the Williams Treaties First Nations with the goal of considering and reflecting their views, perspectives and knowledge in the ongoing oversight on the DN.

2.1.1.1 Construction of the Darlington Used Fuel Dry Storage Facility

In 2001, OPG communicated its intent to construct and operate a used fuel dry storage facility (UFDSF) at the DNGS, renamed to DWMF upon construction. The proposed UFDSF project involved the construction of the UFDSF facility, preparation of DSCs for storage, and placement and monitoring of the DSCs in the storage building. CNSC staff determined that OPG’s proposal required a screening-level EA under CEAA 1992 Footnote 26, before the CNSC could consider OPG’s application under the NSCA. In November 2003, following the Commission’s consideration of the EA screening report Footnote 27 written by CNSC staff, the Commission concluded in the Reasons for Decision that the project was not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects if the mitigation measures identified in the EA screening report were taken Footnote 28.

The EA process identified the need for an EA follow-up monitoring program (FUMP) Footnote 29, which was deemed complete by CNSC staff in 2012 Footnote 30. Please note that OPG refers to FUMPs as an Environmental Monitoring and Environmental Assessment Follow-Up.

2.1.1.2 Darlington New Nuclear Project

In 2007, an EA was initiated under the CEAA 1992 for the proposed Darlington New Nuclear Project. This project encompassed the site preparation and eventual construction and operation of up to four additional nuclear reactors within the DN site. The Federal Minister of Environment referred the EA for the project to a joint review panel (JRP) for assessment Footnote 31.In 2011, the JRP submitted its EA Report to the Minister of the Environment, concluding that the “proposed project was not likely to cause significant adverse effects provided the mitigation measures proposed and commitments made by OPG and the Panel’s recommendations are implemented” Footnote 31. In May 2012, the Government of Canada accepted the intent of all of the JRP’s recommendations. In August 2012, the JRP, as a panel of the Commission issued a 10-year site preparation licence for DNNP. This licence was renewed in 2022.

In December 2021, OPG announced its selection of the General Electric Hitachi BWRX-300 reactor for deployment at the DNNP site and applied for a licence to construct in October 2022. In April 2024, the Commission determined following a public hearing in January 2024 that the EA decision made by the JRP in 2011 Footnote 31 remains applicable to OPG’s selected reactor technology and a new environmental assessment is not required Footnote 25.

A complete project timeline for the Darlington New Nuclear Project can be found on the CNSC’s website: Darlington New Nuclear Project timeline (cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca)

2.1.1.3 Refurbishment and Continued Operation of DNGS

In 2011, an EA was conducted under the CEAA 1992 for the DNGS Refurbishment and Continued Operation Project Footnote 32. The purpose of the project being to refurbish the DNGS to allow it to continue to operate until approximately 2055. The principle works and activities within the scope of the proposed project included the construction of the RWSB and other supporting buildings, the transportation of low and intermediate-level radioactive waste to an off-site management DWMF, and the refurbishment of the CANDU reactors. In 2012, the Commission issued the Record of Proceedings and Decision Footnote 33 and concluded that the proposed project was not likely to cause significant adverse effects.

2.1.2 Current environmental assessment follow-up monitoring program

EA follow-up monitoring programs are designed to validate the predicted environmental effects and the effectiveness of mitigation measures. The CNSC ensures that EA FUMPs that are within the CNSC’s mandate are incorporated into licensing and compliance activities.

2.1.2.1 Darlington New Nuclear Project

As required by CEAA 1992, the CNSC, with the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and Transport Canada as Responsible Authorities, required that OPG establish and implement an EA FUMP Footnote 34. To meet this requirement, as well as other JRP recommendations accepted by the Government of Canada in the EA, OPG has created DNNP Commitments with associated deliverables.

As part of the DNNP Commitment D-P-12.1, which addresses the EA FUMP, OPG has provided an overall EA FUMP Footnote 35, as well as specific methodology reports covering a variety of environmental components; tracked through the completion of DNNP Deliverables D-P-12.2 through D-P-12.9 Footnote 36. In the Commission’s Record of Decision on the Determination of Applicability of Darlington New Nuclear Project Environmental Assessment to OPG’s Chosen Reactor Technology, the Commission outlined the following recommendations related to the EA FUMP:

“The Commission also recommends that in the OPG development and implementation of its EA follow-up program, OPG incorporate, to the extent possible, engagement with the Williams Treaties First Nations and the Métis Nation of Ontario on applicable items (e.g., measures to offset the loss of bank swallows nesting habitat), Indigenous Knowledge, and land use information and data in the program. The Commission expects that CNSC staff continues to support the Williams Treaties First Nations to gather traditional Indigenous Knowledge and land use information and data.”

2.1.2.2 FUMP for the Refurbishment and Continued Operation of DNGS Footnote 37

In the Record of Proceedings and Decision Footnote 33, an EA FUMP was required for the Darlington B Refurbishment and Continued Operation project. OPG developed an EA FUMP in consultation with the CNSC, ECCC and DFO and the public and Indigenous Nations were invited to review the program through a 30-day consultation period Footnote 38. The actions to be completed for the FUMP and the schedule for implementation and reporting are captured in the Integrated Implementation Plan (IIP) Footnote 39. OPG continues to provide periodic updates on the status of the EA FUMP to the CNSC through the IIP process.

2.1.3 Previous environmental protection review completed under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act

2.1.3.1 Darlington Nuclear Generating Station Licence Renewal

In 2015, OPG applied for a 10-year licence to renew its DNGS Operating Licence. An EA under the NSCA was conducted for the licence application Footnote 40. CNSC staff concluded that OPG has and would continue to make adequate provision for the protection of the environment and the health of persons. A two-part public Commission hearing on the licence application was held in August and November 2015 and the Commission approved OPG’s application Footnote 41.

In May 2024, OPG submitted a licence application to renew the power reactor operating licence from December 1, 2025 to November 30, 2055 Footnote 3. The Commission will hold a two-part public hearing in 2025. CNSC staff have prepared this EPR report to inform the licensing decision of the Commission.

2.1.3.2 Darlington Waste Management Facility Licence Renewal

In 2021, OPG applied for a 10-year licence to renew its DWMF Operating Licence. An EPR under the NSCA was conducted for the licence application Footnote 42. CNSC staff concluded that OPG has and would continue to make adequate provision for the protection of the environment and the health of persons. A public Commission hearing on the licence application was held in January 2023 and the Commission approved OPG’s application to renew the license until April 30, 2033 Footnote 43.

2.2 Planned end-state

The following section provides high-level information on the currently planned end-state of the DN site following decommissioning activities. This section is informed by OPG’s PDP for the DN site. The PDP is important to consider as part of CNSC staff’s ongoing oversight for the assessment of environmental and health effects of nuclear facilities and activities.

A PDP is required to be developed by the licensee and submitted to the CNSC for review and acceptance as early as possible in the facility’s lifecycle or the conduct of the licensed activities. The PDP is progressively updated, where needed, to reflect the appropriate level of detail required for the respective licensed activities. The PDP is developed for planning purposes only and the associated cost estimate is used to set aside dedicated decommissioning funding in the form of a financial guarantee. The PDP does not authorize decommissioning and does not provide sufficient details for the assessment of environmental impacts during decommissioning. Prior to the commencement of any decommissioning activities and to support an application for a licence to decommission, a detailed decommissioning plan is required to be developed by the licensee and submitted to the CNSC for review and acceptance.

PDPs for nuclear facilities are updated by the licensee at least every 5 years, considering notable changes relevant to decommissioning, or as requested by the CNSC. The decommissioning strategy and end-state objectives for the DN site are documented in the Darlington Nuclear Site preliminary decommissioning plan Footnote 5 and the preliminary decommissioning plan for the Darlington Waste Management Facility Footnote 4.

OPG’s PDP assumes that the reactor units will be shut down between 2050 to 2056 and the DNGS will be dismantled once decommissioning is approved. A deferred decommissioning strategy has been planned and flexibility is built into the process to cater to the final decision OPG may make with respect to shutdown dates. The DWMF will remain in operation after shutdown of the DNGS reactors and is expected to continue receiving, processing, and storing DSCs during stabilization and storage with surveillance, until all the fuel has been removed. This PDP is the proposed plan for decommissioning the DNGS and since it also addresses the interfaces of the DNGS with the DWMF, which is also located on the DN site, it is referred to as the site PDP. The purpose of the PDP is to define the areas to be decommissioned and the sequence of the principal decommissioning work for the DNGS. The PDP also demonstrates that decommissioning is feasible with existing technology, and it provides a basis for estimating the cost of decommissioning. The PDP describes the final end-state after dismantling, demolition and site restoration, which notes that the site will be free of industrial and nuclear hazards.

In January 2022, OPG submitted the updated DN site PDP. CNSC staff have reviewed the PDP and provided comments and requests to which OPG is required to respond. An updated DN site PDP is expected in 2027. It should be noted that OPG submitted an application to extend the commercial operation date of the DNGS from December 1, 2025 to November 30, 2055 Footnote 3. This application is currently under review by CNSC staff and will require a Commission hearing for decision. Should the Commission grant a licence extension, OPG will be required to submit a revised PDP, including additional decommissioning activities and associated costs for the licence extension.

2.3 Environmental regulatory framework and protection measures

The CNSC has a comprehensive EP regulatory framework which includes the protection of people and the environment and considers both nuclear and hazardous substances, as well as physical stressors (such as noise). Public dose is included in the EP framework. The focus of this section of the EPR report is on the EP regulatory framework and the status of OPG’s environmental protection program (EPP) for the DN site. The results from OPG’s EPP are detailed in section 3.0 of this report.

OPG’s EPP for the DN site was designed and implemented in accordance with REGDOC-2.9.1, Environmental Protection: Environmental Principles, Assessments and Protection Measures (2017) Footnote 44, as well as the CSA Group’s environmental protection standards listed below. The implementation status for these documents is shown in table 2.2. The EPP includes derived release limits (DRLs) and public dose modelling.

| Regulatory document or standard | Status |

|---|---|

| CSA N288.0-22, Environmental management of nuclear facilities: Common requirements of the CSA N288 series of Standards Footnote 45 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.1-14, Guidelines for calculating derived release limits for radioactive material in airborne and liquid effluents for normal operation of nuclear facilities Footnote 46 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.1-20, Guidelines for modelling radionuclide environmental transport, fate, and exposure associated with the normal operation of nuclear facilities Footnote 47 | To be implemented following submissions of revised DRLs (2028) |

| CSA N288.4-19, Environmental monitoring programs at nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 48 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.5-22, Effluent and emissions monitoring programs at nuclear facilities Footnote 49 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.6-12, Environmental risk assessment at Class I Nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 50 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.6-22, Environmental risk assessments at nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 51 | To be implemented November 30, 2026 |

| CSA N288.7-15, Groundwater protection programs at Class 1 nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 52 | Implemented |

| CSA N288.7-22, Groundwater protection and monitoring programs for nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 53 | Implementation Plan to be submitted by December 2, 2024 |

| CSA N288.8-17, Establishing and implementing action levels for releases to the environment from nuclear facilities Footnote 54 | Implemented |

| CNSC REGDOC-2.9.1, Environmental Protection: Environmental Principles, Assessments and Protection Measures, version 1.1 (2017) Footnote 44 | Implemented |

CNSC staff confirm that OPG has implemented programs that are following the relevant EP regulatory documents and standards or has implementation plans in place.

Licensees are also required to regularly report on the results of their EPPs. Reporting requirements are specified in REGDOC-3.1.1, Reporting Requirements for Nuclear Power Plants Footnote 55, REGDOC-3.1.2 Reporting Requirements, Volume I: Non-Power Reactor Class I Nuclear Facilities and Uranium Mines and Mills Footnote 56, the Radiation Protection Regulations Footnote 57 (e.g., for action level (AL) or dose limit exceedances), the licensees’ approved programs and manuals, and the LCH Footnote 58.

OPG is required to submit quarterly safety performance indicator reports, annual reports on environmental protection for the NGS and quarterly reports and annual compliance reports as per REGDOC-3.1.1 Footnote 55 and REGDOC-3.1.2 Footnote 56. These reports are reviewed by CNSC staff for compliance and verification, as well as trending. OPG publishes several of these reports on its website, such as web page Regulatory reporting - OPG Footnote 59.

CNSC staff regularly report on licensee performance to the Commission for activities conducted at the DN site. For example, CNSC staff's regulatory oversight reports (RORs) are a standard mechanism for updating the Commission, Indigenous Nations and communities, and the public on the operation and regulatory performance of licensed facilities. Previous RORs are available on the CNSC regulatory oversight reports web page Footnote 60. CNSC staff may also report to the Commission on significant events, such as unplanned releases to the environment, through an event initial report.

2.3.1 Environmental protection measures

To meet the CNSC’s regulatory requirements under REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44, OPG is responsible for implementing and maintaining EP measures that identify, control and monitor releases of radioactive nuclear and hazardous substances from the DN site, as well as the effects of these substances on human health and the environment. EP measures are an important component of the overall requirement of licensees to make adequate provisions to protect the environment and the health of persons.

This subsection and the following ones under section 2.3 summarize OPG’s EPP for the DN site and the status of each specific EP measure, relative to the requirements or guidance outlined in the latest regulatory document or CSA Group standard. Section 3.0 of this EPR report summarizes the results of these programs or measures against relevant regulatory limits and environmental quality objectives or guidelines, and discusses, where applicable, any interesting trends.

OPG is required to implement an environmental management system (EMS) that conforms to REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44 and to submit an EPP for the DN site. OPG’s EPP includes the following components to meet the requirements and guidance as outlined in REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44:

- EMS (subsection 2.3.2)

- environmental risk assessment (ERA) (subsection 2.3.3)

- effluent and emissions control and monitoring (section 2.3.5)

- derived release limits and operating release limits

- air emissions and liquid effluent monitoring

- environmental monitoring program (EMP) (section 2.3.6)

- ambient air monitoring

- fruits and vegetables monitoring

- animal feed monitoring

- eggs and poultry monitoring

- milk monitoring

- soil and sand monitoring

- surface water monitoring (lake and water supply plants)

- well water monitoring

- groundwater monitoring

- sediment monitoring

- fish monitoring

Section 3.0 of this EPR report summarizes the results of these programs or measures against relevant regulatory limits and environmental quality objectives or guidelines, and discusses, where applicable, any notable trends.

2.3.2 Environmental management system

An EMS refers to the management of an organization’s environmental policies, programs and procedures in a comprehensive, systematic, planned, and documented manner. It includes the organizational structure as well as the planning and resources to develop, implement and maintain an EP policy. The EMS serves as a management tool to integrate all of a licensee’s EP measures in a documented, managed and auditable process in order to:

- identify and manage non-compliances and corrective actions within the activities through internal and external inspections and audits

- summarize and report on the performance of these activities both internally (licensee management) and externally (Indigenous Nations and communities, the public, interested stakeholders, and the Commission)

- train personnel involved in these activities

- ensure the availability of resources (that is, qualified personnel, organizational infrastructure, technology and financial resources)

- define and delegate roles, responsibilities, and authorities essential to effective management

OPG has established and implemented a corporate EMS for the DN site in accordance with REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44 and is also registered and certified under the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard 14001:2015 (a standard that helps an organization achieve the intended outcomes of its EMS). CNSC staff review OPG’s annual internal audits; management reviews; and environmental goals, targets and objectives to ensure compliance with REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017). While the CNSC does not consider ISO 14001 certification as part of the criteria for meeting the requirements of REGDOC-2.9.1, the results of these third-party audits are reviewed by CNSC staff as part of the compliance program. CNSC staff also review the status of OPG’s annual goals, targets and objectives and the implementation of the EMS as part of their review of the annual reports on EP.

The results of these reviews demonstrate that OPG’s EMS for the DN site meets the CNSC requirements as outlined in REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44. The implementation of the EMS ensures that OPG continues to improve environmental performance at the DN site.

2.3.3 Environmental risk assessment

An ERA of nuclear facilities is a systematic process used by licensees to identify, quantify and characterize the risk posed by contaminants and physical stressors in the environment on human and other biological receptors, including the magnitude and extent of the potential effects associated with a facility. The ERA serves as the basis for the development of site-specific EP measures and the results from the ERA updates determine whether the facility’s effluent monitoring and EMP are effective. The results of these programs, in turn, inform and refine future revisions of the ERA.

In March 2021, OPG submitted their 2020 Environmental Risk Assessment for the DN site Footnote 61 (2020 ERA) in accordance with the requirements set out in CSA N288.6-12 Footnote 50, and REGDOC 2.9.1 Footnote 44 which stipulates that licensees must review and revise their ERA every 5 years. OPG’s ERA submission is site-wide and encompassed the entirety of the DN site, including the DWMF. The DN site-wide 2020 ERA included an ecological risk assessment (EcoRA) and a human health risk assessment (HHRA) for nuclear and hazardous contaminants and physical stressors. The 2020 ERA included risks associated with the DN site, which includes the DNGS and DWMF, based on effluent and environmental monitoring data for the period between 2016 to 2019.

The ERA was performed in a stepwise manner, as follows:

- quantify the releases (of COPCs) to the environment from current (see section 3.1) and future activities

- identify the environmental interactions of the current and expected releases of COPCs, and COPC exposure pathways in the environment

- identify predicted COPC exposure for ecological and human receptors

- identify potential effects to receptors

- quantify the releases (of COPCs) to the environment from current (see section 3.1) and future activities

- identify the environmental interactions of the current and expected releases of COPCs, and COPC exposure pathways in the environment

- identify predicted COPC exposure for ecological and human receptors

- identify potential effects to receptors

- determine whether the environment and health and safety of persons is and will continue to be protected

CNSC staff reviewed the 2020 site-wide ERA and required additional information in order to verify whether the ERA was compliant with requirements in REGDOC 2.9.1 and CSA N288.6 Footnote 62. In October 2021, OPG submitted a revised ERA report, taking into consideration CNSC staff comments Footnote 63. CNSC staff reviewed OPG’s revised ERA and found it to be compliant with CSA N288.6-12 Footnote 50.

OPG’s findings from the revised 2020 ERA are summarized in table 2.3 below. CNSC staff reviewed the revised ERA and have found that no new risks have emerged since the previous ERA and that unreasonable risks to human health and the environment attributable to DNGS and DWMF operations are unlikely.

The findings of the revised 2020 ERA are summarized in table 2.3. Adverse effects to ecological and human health due to releases of COPCs to the air and water from the DN site were found to be negligible.

| Type | Members of the public | Aquatic and terrestrial biota |

|---|---|---|

| Radiological | The annual dose to the critical receptor was well below the public dose limit and there were no concerns | There were no exceedances of the radiation dose benchmarks for ecological receptors. |

| Hazardous | There are negligible releases of hazardous COPCs from the facility. No adverse impacts expected on members of the public. | There are negligible releases of hazardous COPCs from the facility. However, concentrations of certain metals in soil, in a localized area were above the soil quality criteria. However, no adverse population level impacts expected on aquatic and terrestrial biota. |

| Physical stressors* | There are no adverse impacts expected from physical stressors associated with operations at the facility. | There are no adverse impacts on biota expected from physical stressors associated with operations at the facility. |

2.3.4 Effluent and emissions control and monitoring

Controls on environmental releases are established to provide protection to the environment and to respect the principles of sustainable development and pollution prevention. The effluent and emissions prevention and control measures are established based on industry best practice, the application of optimization of protection (such as in design) and of as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) principles, the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) guidelines, and results of the licensee’s ERAs.

OPG has controls in place to minimize airborne emissions and waterborne effluents for radiological and non-radiological COPCs, and to ensure that releases are within regulatory limits and ALARA.

OPG has implemented an effluent and emission monitoring program in compliance with REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44 and the relevant standards, including CSA N288.5-22, Effluent and emissions monitoring programs at nuclear facilities Footnote 49 and CSA N288.0-22, Environmental management of nuclear facilities: Common requirements of the CSA N288 series of Standards Footnote 45. This program contains DRLs and ALs. The DRLs represent the maximum acceptable level of emitted contaminants from the processes at the DN site and are derived from the dose limit for members of the public (that is, 1 millisievert [mSv] per year). In addition, the DN site has established ALs that serve as an early warning of potential loss of control of the EPP.

Based on compliance activities, CNSC staff have found that the effluent and emission monitoring program currently in place for the DN site continues to protect human health and the environment.

2.3.5 Environmental monitoring program

The CNSC requires each licensee to design and implement an EMP that is specific to the monitoring and assessment requirements of the licensed facility and its surrounding environment. The program is required to:

- measure contaminants in the environmental media surrounding the facility or site

- determine the effects, if any, of the facility or site operations on people and the environment

- serve as a secondary support to effluent and emission monitoring programs to demonstrate the effectiveness of emission controls

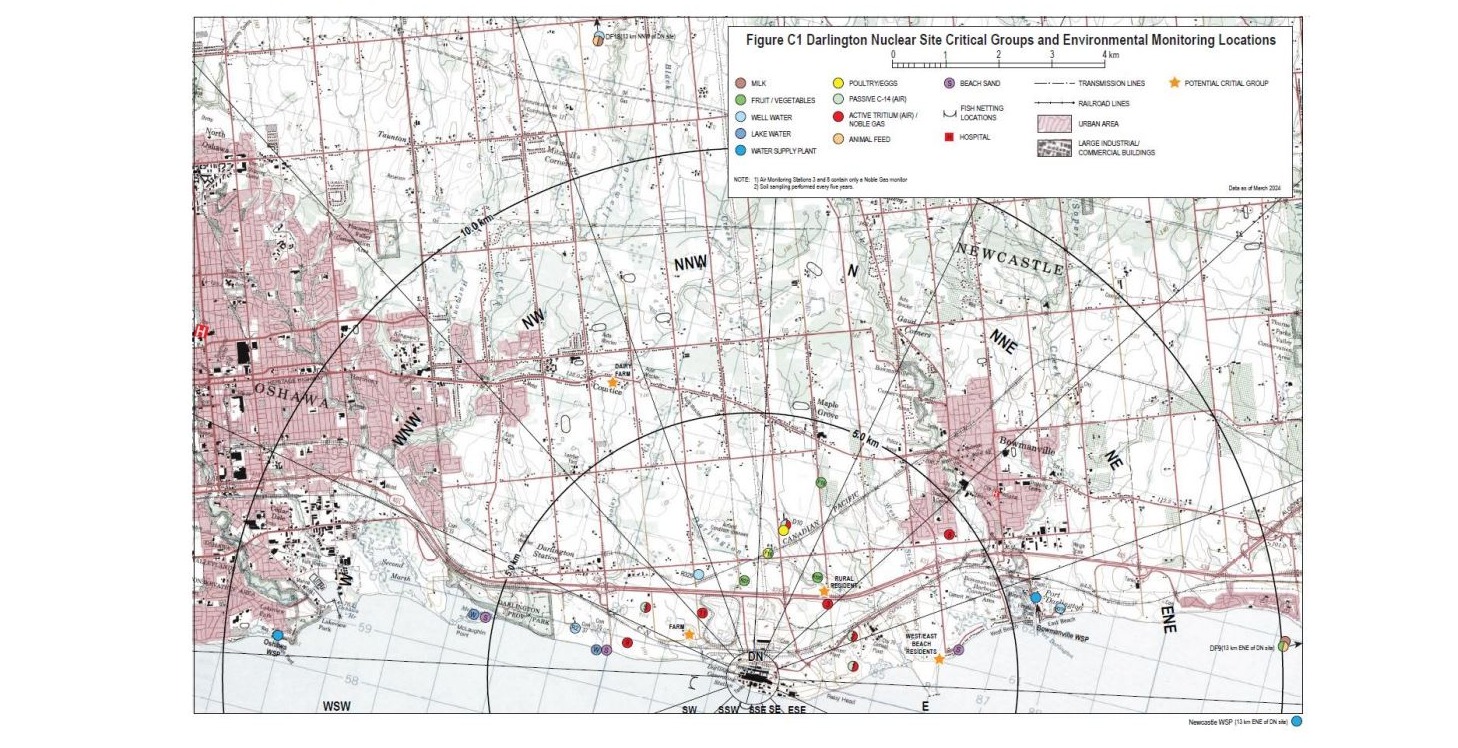

More specifically, the program must gather the necessary environmental data to calculate the public dose and demonstrate compliance with the public dose limit found in the Radiation Protection Regulations Footnote 64 of 1 mSv per year. The program design must also address the potential environmental interactions identified at the facility or site. Radionuclides are the major focus at the DN site, though hazardous substances environmental compliance approval (ECA) are included within monitoring activities associated with liquid discharges and air emissions. OPG’s EMP for the DN site consists of the following components:

- ambient air monitoring

- fruits and vegetables monitoring

- animal feed monitoring

- eggs and poultry monitoring

- milk monitoring

- soil and sand monitoring

- surface water (lake and water supply plants)

- well water monitoring

- groundwater monitoring

- sediment monitoring

- fish monitoring

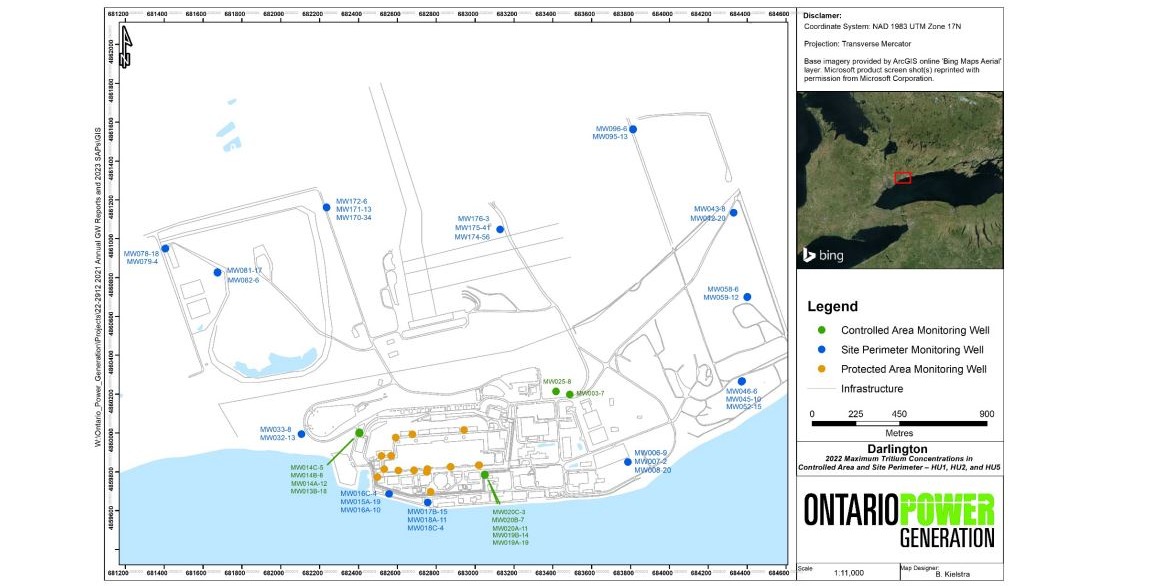

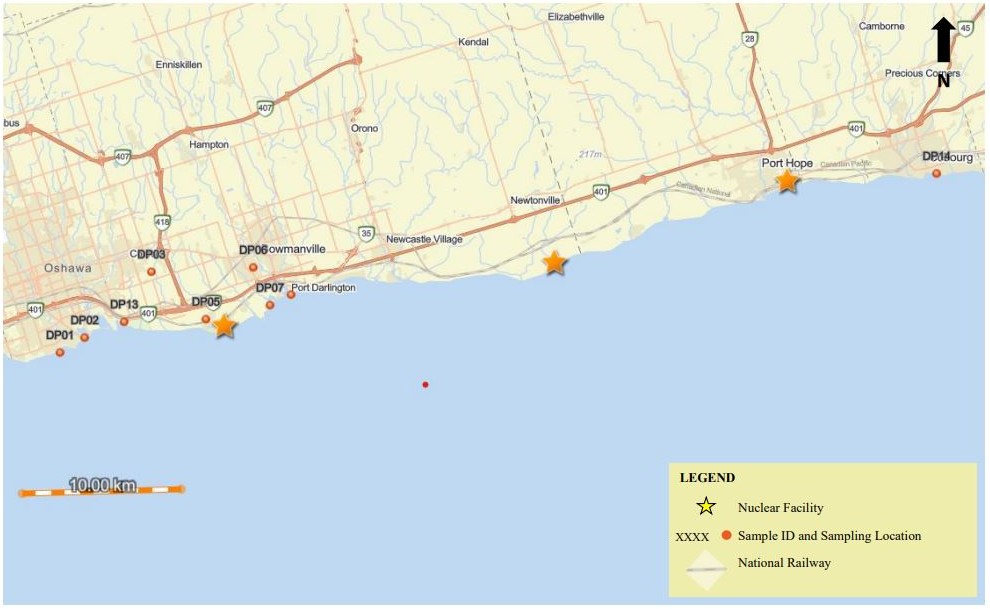

Monitoring frequency and parameters are specified in OPG EMP reports Footnote 59. The sampling locations are shown on the map below figure 2.1.

OPG is required to maintain its EMP to comply with REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44 and relevant standards, including CSA N288.4-19, Environmental monitoring programs at nuclear facilities and uranium mines and mills Footnote 48 and CSA N288.0-22, Environmental management of nuclear facilities: Common requirements of the CSA N288 series of Standards Footnote 45.

Based on compliance activities and technical assessments, CNSC staff have found that OPG is compliant with REGDOC-2.9.1 (2017) Footnote 44 and continues to implement and maintain an effective EMP for the DN site that adequately protects the environment and the health and safety of persons.

2.4 Requirements under other federal or provincial regulations

A core element of the CNSC’s requirement for an EMS is the identification of all regulatory requirements applicable to the facility, whether pursuant to the NSCA or other federal or provincial legislation. The EMS must ensure that programs are in place to respect these requirements.

2.4.1 Greenhouse gas emissions

While there is a range of broadly applicable federal environmental regulations (for example, petroleum products storage tanks, environmental emergency regulations), the management of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has been identified as a national priority.

Under the federal Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999) Footnote 65, OPG is required to monitor and report on GHG emissions. Facilities that emit more than the emission reporting threshold (that is, 10,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent) on an annual basis must report their GHG emissions to ECCC. In the case of the DN, site CO2 releases remained below the reporting threshold from 2019 to 2023 Footnote 6 Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10.

The CNSC maintains a collaborative working relationship with ECCC through a formal memorandum of understanding (MOU) Footnote 66, which includes a notification protocol. An exceedance of the GHG emissions reporting threshold would be included under this notification protocol. This ensures that a coordinated regulatory approach is achieved to meet all federal requirements associated with EP, including GHGs.

2.4.2 Ozone depleting substances

In accordance with the Federal Halocarbon Regulations, 2022 Footnote 67, OPG is required to provide a semi-annual halocarbon release report to ECCC on the release of halocarbons of an amount greater than 10 kilograms (kg) but less than 100 kg from any system, container or equipment at the DN site. In the event of a release that surpasses 100 kg, OPG would be required to report the releases to ECCC within 24 hours and ECCC would inform the CNSC through the notification protocol of the CNSC-ECCC MOU. OPG would then be required to submit a follow-up report to ECCC within 30 days of the release detailing the circumstances leading to the release and the corrective and preventive actions taken to prevent a reoccurrence.

OPG has reports as required the information needed for the DN site for the assessed period (2019–2023).

2.4.3 Sulphur dioxide emissions

Under the authority of CEPA 1999 Footnote 65, OPG is also required to estimate the total sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions from the DN site and report to the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI), provided that the reporting requirements are met. The sulphur dioxide emissions at the DN site remained below the NPRI reporting threshold for the assessed period (2019–2023). OPG is still reporting its sulphur dioxide releases in its annual environmental monitoring report Footnote 6 Footnote 7 Footnote 8 Footnote 9 Footnote 10.

2.4.4 Other environmental compliance approvals

Non-radiological liquid effluent is monitored in accordance with the provincial ECA requirements. Non-radiological liquid effluent from the radioactive liquid waste management system must comply with ECA requirements. COPCs not addressed by the ECA are assessed through the ERA to determine whether they merit additional regulatory oversight.

Non-radiological airborne emissions are required to be in compliance with provincial regulation O. Reg. 419/05 Footnote 68, which is met by complying with the ECA for Air and Noise. OPG did not report any non-compliances for its ECA. An Emissions Summary and Dispersion Modelling report is used to document and maintain compliance with O. Reg. 419/05 Footnote 68.

2.4.5 Fisheries Act Authorization

In October 2023, DFO and the CNSC signed a revised MOU outlining areas for cooperation and administration of the Fisheries Act Footnote 69, which aims to conserve and protect fish and fish habitat across Canada.

The CNSC-DFO MOU focuses on sections 34 and 35 of the Fisheries Act, which state that no person shall carry on any work, undertaking or activity that could cause the death of fish and/or harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat, unless the Minister of DFO issues a Fisheries Act Authorization (FAA). This authorization, if granted, includes terms and conditions to avoid, mitigate, offset (that is, counterbalance impacts) and monitor the impacts on fish and fish habitat resulting from a specific project.

2.5 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and federal partners consideration of climate change

The CNSC’s regulatory framework requires licensees and proponents to consider climate change primarily through requirements related to EAs and safety assessments. These assessments take place throughout the licensing lifecycle as part of the licence application, licence renewal and periodic safety review (PSR) process.

CNSC staff’s consideration of climate change during these assessments may include examining whether climate change is considered in the analysis of external hazards and environmental parameters such as meteorological and hydrological parameters used in the design, evaluation and upgrade of a nuclear facility, and whether a licensee has applied the defence-in-depth principle in its design with sufficient safety margin.

Specifically, climate change considerations are included in the following mechanisms in the regulatory framework:

Environmental assessment

Previously under CEAA 2012 and currently under the IAA, proponents must assess the climate change impact on a project itself and thereby the surrounding environment, over the lifetime of the facility. As noted in section 2.1, the DN site has undergone numerous EAs that have demonstrated that, with mitigation measures implemented, climate change, as well as the anticipated increases in the magnitude and frequency of external hazards due to climate change, would not likely have impact on the project that would lead to residual adverse effect. The most recent EAs Footnote 32 Footnote 70 Footnote 71 for the DN site conducted in 2007 and 2011 assessed the impact of climate change and are discussed further in Section 3.2.7.

Periodic safety reviews

Licensees for nuclear power plants are required to conduct PSRs to evaluate the design, condition and operation of the facility. Probabilistic Safety Assessment (PSA), as one of the safety factors evaluated in the PSR, includes analysis of external hazards, such as flooding, and their impact on a facility. As part of the 5-year cyclical review process, CNSC staff review the PSA and ensure that up-to-date hazard information is included.

In OPG’s latest hazard analysis report Footnote 72, flood hazards (including probable maximum flood due to a combination of probable maximum precipitation (PMP), 1:100 year lake level and storm surge) were screened out from additional probabilistic safety assessment, indicating that risk due to external flood hazards is low.

Environmental risk assessment

As described further in section 2.3.3, an ERA (updated in a 5-year review cycle) evaluates risk posed by contaminants and physical stressors to the environment under normal operating conditions, taking into consideration recent monitoring data (including meteorological parameters) and new scientific knowledge. The latest ERA update Footnote 63 graphically evaluated the monthly variability of temperature and precipitation, as well as the annual prevailing wind distribution, based on latest monitoring data. Thermal plume monitoring results were presented and OPG demonstrated that it is unlikely there are any effects arising from the thermal plume in the lake for juvenile or adult stages of any fish species. CNSC staff will continue to assess potential thermal impacts to aquatic receptors from site discharges keeping in mind any environmental changes due to climate change.

CNSC and ECCC collaboration

The CNSC and ECCC have an MOU Footnote 66 in place that includes collaboration related to climate change. For example, ECCC contributes expertise on projection of climate change and estimations of extreme rainfall intensity-duration-frequency curve and probable maximum precipitation (PMP) for various sites to CNSC staff. This informs CNSC staff’s technical reviews.

ECCC also has the mandate to monitor and provide meteorological data to Canadians, to conduct scientific research regarding the mechanism and effects of climate change, and to develop science-based guidance on assessment of climate change for application when projects are subject to federal impact assessments. The Strategic Assessment of Climate Change guidance Footnote 73 includes specific guidance on net zero plans, calculation of GHG emissions/intensity and resiliency.

Further information on how the CNSC assesses the impacts of climate change on nuclear safety in Canada can be found at Climate Change Impact Considerations.

3.0 Status of the environment

This section provides a summary of the status of the environment around the DN site. It starts with a description of the nuclear and hazardous releases to the environment (section 3.1), followed by a description of the environment surrounding the DN site and an assessment of any potential effects on the different components of the environment as a result of exposure to these contaminants (section 3.2).

CNSC staff regularly review the potential effects on environmental components through annual reporting requirements and compliance verification activities, as detailed in other areas of this report. This information is reported to the Commission in the sections on EP in licensing commission member documents and annual RORs. The EMP reports submitted by OPG for the DN site are made publicly available and can be viewed on OPG’s website: Regulatory reporting - OPG Footnote 59.

3.1 Releases to the environment

Radioactive nuclear and hazardous substances that have the potential to cause an adverse effects to ecological or human receptors are identified as COPCs. The ways in which COPCs could find their way to the different receptors considered by the ERA are called “exposure pathways.”

Figure 3.1 illustrates a conceptual model of the environment around a nuclear site to show the relationship between releases (airborne emissions or waterborne effluent) and human and ecological receptors. This graphic is meant to provide an overall conceptual model of the releases, exposure pathways and receptors for the DN site and thus should not be interpreted as a complete depiction of the DN site and its surrounding environment.

Releases from the DWMF are significantly lower than those from the DNGS, and so emissions from the DWMF should be considered as a small fraction of the overall emissions and releases from the DN site. The specific releases and COPCs associated with the DN site are explained in detail in the following subsections.

3.1.1 Licensed release limits

OPG uses DRLs and ALs, approved by the CNSC, to control radiological effluent and emission releases from the site as discussed in section 2.3.5. A DRL for a given radionuclide is the release rate that would cause an individual of the most highly exposed group to receive a dose equal to the regulatory annual dose limit of 1 mSv.

3.1.2 Airborne emissions

OPG controls and monitors airborne emissions from the DN site to the environment under its effluent monitoring program. This program is based on CSA N288.5-22, Effluent and emissions monitoring programs at nuclear facilities Footnote 49 and includes monitoring of both nuclear and hazardous emissions.

3.1.2.1 DN site radiological airborne releases

As part of OPG’s effluent monitoring program, releases to the atmosphere are collected and are routinely analyzed for tritium, elemental tritium, carbon-14 (C-14), iodine-131 (I-131), noble gases and particulates. The results are compared against DRLs developed by OPG and approved by the CNSC to ensure release limits to the environment will not exceed the annual regulatory public dose limit of 1 mSv. As shown in table 3.1, the average radiological emissions from the DN site remain at a very small fraction of the DRLs.

| Parameter (Bq/yr) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | DRLs Footnote 58 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tritium oxide | 2.0x1014 | 1.9x1014 | 2.6x1014 | 2.2x1014 | 5.3x1014 | 3.91x1016 |

| Elemental tritium* | 2.5x1013 | 1.5x1013 | 1.7x1013 | 9.2x1013 | 1.3x1015 | 6.26x1017 |

| Noble gas** | 5.0x1013 | 2.4x1013 | 2.7x1013 | 2.2x1013 | 4.4x1013 | 3.46x1016 |

| Iodine-131 | 1.4x108 | 1.5x108 | 1.5x108 | 1.4x108 | 1.2x108 | 1.74x1012 |

| Particulate gross beta-gamma | 2.6x107 | 3.1x107 | 2.0x107 | 2.9x107 | 2.8x107 | 5.51x1011 |

| Carbon-14 | 9.7x1011 | 8.3x1011 | 1.2x1012 | 1.2x1012 | 1.1x1012 | 7.68x1014 |

* Emissions from Darlington Tritium Removal Facility

** Airborne noble gas emission units are in becquerel- Mega electron-volt (Bq-MeV)

3.1.2.2 DWMF radiological airborne releases

Under normal operating conditions, radiological airborne releases are unlikely to occur during transfer and storage of sealed and welded DSCs at the DWMF. However, there is a small potential for airborne emissions at the DWMF resulting from DSC processing operations, such as welding and vacuum drying. The DSC processing building has a dedicated High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) air filtered active ventilation system. Airborne particulate contamination, if present, would be effectively removed by the HEPA filters in the active ventilation system. Past PWMF, WWMF and DWMF operating experience demonstrates that particulate emissions in exhaust from DSC processing operations have been typically below the Minimum Detectable Activity. OPG website, under regulatory reporting Footnote 74

3.1.2.3 DN site non-radiological releases

The main sources of non-radiological releases at the DN site are the standby diesel generators onsite. These sources release small quantities of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide. In addition, hydrazine, morpholine and ammonia are used in the feedwater system to prevent corrosion and are released in small quantities through controlled venting. Ozone-depleting substances are used in refrigeration systems, leaks are minimized through routine maintenance of equipment and inspections.

Non-radiological air emissions from the DN site are controlled in accordance with provincial ECA requirements. Dispersion modelling was used to predict the maximum concentrations of COPCs at the property line of the DN site. OPG did not report any ECA non-compliances to the provincial regulator or the CNSC on during the 2019-2023 period.

3.1.2.4 DWMF non-radiological releases

The potential for airborne hazardous substance releases at the DWMF is negligible. Paint touch-up operations for the DSCs involve a minimal amount of paint quantities and paint aerosols from the paint bays, which are removed through filters before exhausting into the active ventilation system. Welding fumes from DSC seal-welding operations are also exhausted through the HEPA filtered active ventilation system. The emissions from the welding operations are also negligible.

3.1.2.5 Findings

Based on CNSC staff’s review of the results of the air emissions monitoring program at the DN site, CNSC staff have found that OPG’s air emissions to the environment from the DN site have remained below the CNSC-approved licence limits throughout the reporting period (2019 to 2023). CNSC staff confirm that OPG continues to provide adequate protection of people and the environment from air emissions.

3.1.3 Waterborne effluent

OPG controls and monitors liquid (waterborne) effluent from the DN site to the environment under its implementation of the effluent monitoring program. This program is based on CSA N288.5-22, Effluent and emissions monitoring programs at nuclear facilities Footnote 49 and includes monitoring of radiological and hazardous releases.

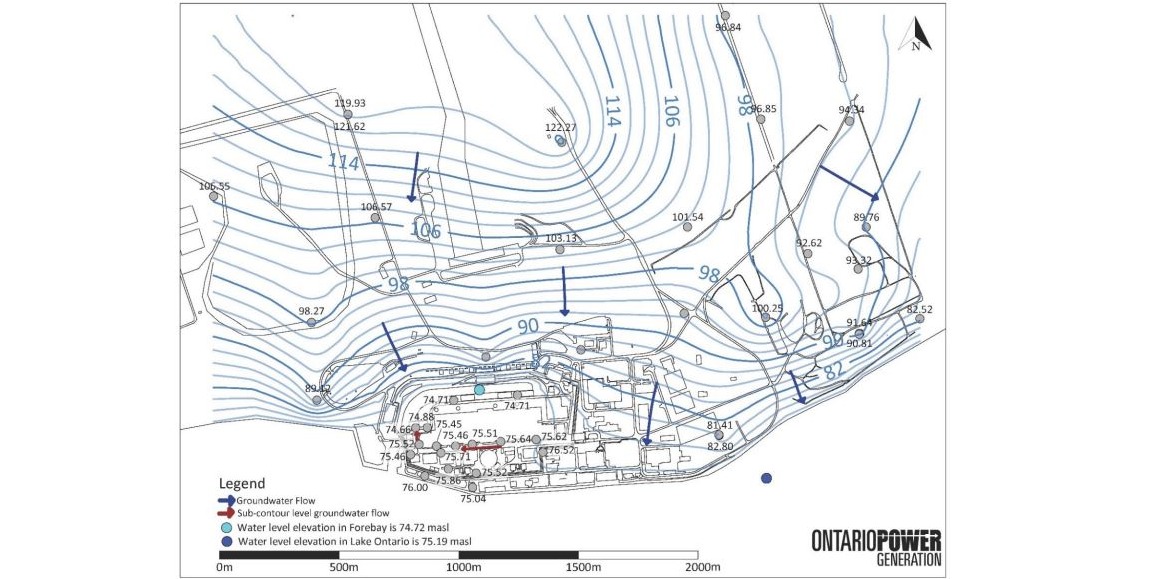

The DN site is located on the north shore of Lake Ontario. Waterborne effluent from the DN site is discharged into the CCW system through either the intake forebay or directly into the CCW discharge duct. The two exceptions are effluent from the domestic sewage system which goes to the Courtice Water Pollution Control Plant, and stormwater which is discharged to Lake Ontario through the storm sewers or drainage swales/creeks.

3.1.3.1 Active Drainage System

The active drainage system collects active (radiological) effluent waste from the drains in the reactor building, the Reactor Auxiliary Bay, the Central Service Area, the Fuelling Facilities Auxiliary Areas, the chemical laboratory sink, the Heavy Water Management Building, and the Tritium Removal Facility. The active liquid waste is directed to the receiving tanks of the radioactive liquid waste management system. The activity in the liquid waste may include tritium, carbon-14, gross alpha and gross beta-gamma (such as cesium-134, cesium-137, cobalt-60 (Co-60) or strontium-90). The active drainage system includes filters and ion exchange columns to purify the waste. After treatment the waste is sampled and chemically analyzed to ensure it meets radioactive and chemical limits prior to discharge. The treatment can also include the addition of sodium bicarbonate and calcium bicarbonate for hardness adjustment and potassium hydroxide for pH adjustment, if required. Radioactivity monitors on the discharge piping automatically stop discharge flow if the detected activity is above specified limits.

3.1.3.2 Inactive Drainage System

Building effluents from inactive areas in all four units, and from the Central Service Area, are collected and combined in a common header prior to discharging to two lagoons (each approximately 4000 m3) operated in series. Forced aeration occurs in the first lagoon to promote mixing and reaction between air and low levels of hydrazine. The effluent from the first lagoon overflows to the second lagoon, which allows sufficient retention time for settling. The lagoon water eventually discharges to the Forebay, to be circulated with CCW and eventually discharged.

3.1.3.3 Stormwater Management System

The Stormwater Management System, or Yard Drainage System, collects storm runoff from the entire DN site and discharges to Lake Ontario either directly through the storm sewer drainage system or through drainage swales/creeks/retention pond via culverts which eventually discharge to the Lake. Stormwater and foundation drainage is regulated by the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) under the Environmental Protection Act Footnote 75 and the Ontario Water Resources Act Footnote 76. Site stormwater works are under the site ECA No. 0585-D4KP24 for industrial sewage works Footnote 77. The stormwater works are designed as per the ECA requirement to ensure that stormwater is properly managed to prevent erosion, flooding, and degradation of receiving water bodies. In the case that the stormwater discharge at the facility were to exceed a provincial limit, OPG would be required to report this exceedance to the CNSC as required under REGDOC-3.2.1, Public Information and Disclosure Footnote 78. To date, the CNSC has not received any reports of exceedances for stormwater discharge at the DN.

As part of OPG’s effluent monitoring program, samples of waterborne effluent are collected and routinely analyzed for tritium, carbon-14 and gross beta/gamma. As per table 3.2, the annual radiological waterborne releases from the DN site remain a very small fraction of the licensed DRLs. From 2019 to 2023 there have been no DRL (regulatory limit) exceedances.

| Parameter (Bq/yr) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | DRL Footnote 58 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tritium oxide | 1.0x1014 | 1.2x1014 | 1.9x1014 | 2.0x1014 | 2.7x1014 | 6.36x1018 |

| Gross beta/gamma | 2.3x1010 | 2.5x1010 | 1.6x1010 | 9.3x109 | 1.7x1010 | 3.47x1013 |

| Carbon-14 | 3.8x108 | 3.8x108 | 1.9x109 | 9.7x108 | 2.2x108 | 6.97x1014 |

3.1.3.4 Findings

CNSC staff have found that OPG’s reported liquid effluent discharged to Lake Ontario from the DN site remained below the CNSC’s approved licence limits throughout the reporting period 2019 to 2023.

CNSC staff are satisfied that OPG is taking the appropriate measures at the DN site, as mentioned above, to effectively control and reduce concentrations and loadings of nuclear and hazardous substances in waterborne effluent.

3.2 Environmental effects assessment

This section presents an overview of the assessment of predicted effects from licensed activities on the environment and the health and safety of persons. CNSC staff reviewed OPG’s assessment of current and predicted effects on the environment and health and safety of persons due to licensed activities included in the ERA (see subsection 2.3.3) for the DN site.

To inform this section of the report, CNSC staff reviewed OPG’s 2020 ERA Footnote 61 Footnote 63, as well as annual reports submitted between 2016 and 2022 inclusively Footnote 9 Footnote 10 Footnote 11 Footnote 12 Footnote 13 Footnote 14 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 Footnote 17 Footnote 18 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 79 Footnote 80.

While CNSC staff conducted a review for all environmental components, only a selection of components is presented in detail in the following subsections. The environmental components were selected based on regulatory requirements, facility type, and geographic context; some were also included because they have historically been of interest to the Commission, Indigenous Nations and communities and the public.

3.2.1 Atmospheric environment

An assessment of the atmospheric environment requires OPG to characterize both the meteorological conditions and the ambient air quality at the DN site.

3.2.1.1 Meteorological conditions

Meteorological conditions, such as temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and precipitation are monitored to assess the extent of the atmospheric dispersion of contaminants emitted to the atmosphere and the rates of contaminant deposition. Meteorological information is also used to determine predominant wind directions, which are used to identify critical receptor locations from the air pathway. Meteorological data were collected from stations within the site, and in local and regional areas, such as the Bowmanville climate station.

The DN site is in southern Ontario on the north shore of Lake Ontario. In Southern Ontario, the climate is influenced by the Great Lakes which results in uniform precipitation amounts year-round, delayed spring and autumn, and moderate temperatures in winter and summer.

3.2.1.2 Ambient air quality

Radiological

Samples of air are collected to monitor the environment around the DN site. These samples are analyzed for tritiated water (HTO), C-14, and noble gases (argon-41, xenon-133, xenon-135 and iridium-192) and the results are used in the calculation of public dose. Background samples are also collected for the dose calculations.

There are six active tritium-in-air samplers (measuring HTO) around the DN site which are collected and analyzed monthly. The background concentration of HTO in air is measured at Nanticoke, Ontario which is considered to be far from the influence of nuclear stations. The levels of HTO observed in the environment depend on station emissions, wind direction, wind speed, ambient humidity and seasonal variations. Fluctuations from year to year are expected even if site HTO emissions remain similar. There were no statistically significant trends over the past 10 years, and the highest annual average for HTO in air was in 2023 which was 5.0 Bq/m3 Footnote 9. In 2023, HTO in air measured at Nanticoke was <0.1 Bq/m3. The annual average HTO in air measured at the background location in recent years has been at or below the active sampler detection limit

Carbon-14 in air is monitored at four boundary locations for the DN site. Samples are analyzed after each quarter. There were no statistically significant trends over the past 10 years, and the highest annual average for Carbon-14 in air in 2022 was 240 Bq/kg-C (see details in Section 3.2.6.1 for information on the risks) Footnote 4. Carbon-14 is naturally occurring in the environment but is also a by-product of past nuclear weapons testing from the early 1960s. Carbon-14 background concentrations around the world are decreasing as weapons test carbon-14 levels naturally decay over time. The annual average carbon-14 in air concentration observed at the Nanticoke EMP background location in 2022 was 205 Bq/kg-C Footnote 9.

External gamma radiation doses from noble gases and iridium-192 are measured using sodium iodide spectrometers set up around DN site. There are 8 detectors around the DN site that monitor the dose rate continuously. Natural background dose has been subtracted from noble gas detector results. The annual boundary average noble gas dose rate is estimated from the monthly data from each detector. The DN boundary average dose rates for Ar-41, Xe-133, Xe-135, and Ir-192 are typically below the detection limits Footnote 9.

Chemicals in air

The main sources of atmospheric emissions result from boiler chemical emissions and fuel combustion. Boiler treatment chemicals including hydrazine, morpholine and degradation products are used within the feedwater system to prevent corrosion in the boilers. These chemicals are released to the atmosphere through controlled boiler venting. Combustion emissions result from the Auxiliary Heating Steam Facility, Standby Generators, Emergency Power Generators, and minor sources. These systems release carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, suspended particulate matter, trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

As part of their 2020 ERA, OPG reviewed the results of the 2016-2019 Emission Summary and Dispersion Modelling Reports (ESDM). All modelled contaminants remained below the criteria for air quality from 2016 to 2019 Footnote 63. The estimated maximum 1-hour (hr) nitrogen oxides (NOx) concentration at the property line was 526 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3), exceeding the 1-hr ambient air quality criteria (AAQC) of 400 μg/m3. This exceedance occurred in 2016, when a standby generator operated for up to 75 hrs during testing. This is a rare event as normally the standby generators operate within the 60 hr per annum limit, and in all years other than 2016, the modelled maximum Point of Impingement (POI)* values for NOx are all below the AAQC. Since there was an occurrence where NOx exceeded criteria, NOx was carried forward as an air COPC as part of their ERA.

*A POI is the point at which a contaminant contacts the ground or a building

Physical Stressors